Bracelet Wearers

Military men have always been clannish. This is partly due to the

armed forces structure, and partly due to the uniquely shared

experience of organized warfare. The uniform and distinctive

insignia, which distinguishes unit members, functions both to

mark them as one of many and to bond them as a unified whole,

which is greater than the sum of its parts. Despite the

stereotypic perceptions to the contrary, the motive behind

uniformity is not to depersonalize the individual, but to

subordinate his autonomy to the greater sovereignty, to adapt his

dedication to a broader application, to utilize his assets for a

higher concern. Soldiers have, nevertheless, retained their

separate identity, and have somehow always personalized their

missions.

|

hat angles worn by WWII soldiers

armor (left) and infantry (right)

|

|

The most obvious personalization is the acquisition of skill

badges (also known as ticket-punching trash) and awards

for valor or merit (getting gonged with fruit-salad), which distinguishes one trooper's performance from

another. Devices, from hershey bars and crossed

idiot-sticks to flying ice-cream cones and

olympic torches, serve as overt recognition of

credibility or authenticity. The wearing of fraternal society,

athletic achievement, or school graduation finger-rings by

ring-knockers advertises one's membership in an

exclusive subgroup. Paratroopers formed the habit of cutting

through the back of their consummate rings, including wedding

bands, so as not to lose a finger if the ring accidentally caught

on something while exiting an aircraft. Even among equivalent

ranks, specialized occupations, and elite organizations,

individuation persists as one entity or another strives to

achieve or surpass, so as to obtain some privilege or merit, from

a guidon streamer to an honors' brassard or trophy. Sometimes it

simply gets down to making a fashion statement by

tilting the hat slightly off-center or by wearing a military

press creased blouse. Some units promoted esprit-de-corps by encouraging off-duty unit-specific clothing, like

sports attire, but the team jacket for most veterans is

their last fatigue shirt with combat designations. The term

mufti refers to an obviously regimented person dressed

in civvies as if such informality were the

designated uniform. Tribes and coteries have long identified

themselves with one or another form of skin art, and the

military tattoo serves the same function, but with a mixed

blessing. The airborne school's black hat instructors

tormented anyone imprudent enough to acquire a parachutist's

tattoo before qualification with a great deal of additional

special training. Members of elite units in

Vietnam demonstrated their intractable commitment by indelibly

marking themselves with their Ranger (Biet Dong Quan)

badge or a defiant legend, such as kill

communists (sat cong); knowing full well that

they were guaranteed no mercy or other consideration if captured.

The Vietnam War was replete with adaptive personalizations ...

some of which became institutionalized. The war began with full-color insignia on European-style fatigues, evolved through three

types of jungle bags (which were a light-weight

adaptation of the World War Two paratrooper's outfit), and

concluded with a tropical battle-dress uniform in

woodland camouflage pattern. Special units wore

leopard-spotted and tiger-striped camouflage,

and almost everyone tried to do something different with their

headgear ... from tailored bush (boonies) hats and

camouflage berets (headshrinkers) to side-pinned safaris

and cowboy patterns. Only new meat was

uncool enough to wear a semblance of

recognizably regulation attire! During the brotherhood

ceremony of cutting-off the ribbon-tails from the beret, after

the unit returned to base camp, as a signal of having been under

fire together, reminded me of the dubbing ritual of conferring

knighthood ... because the recipient willingly submits himself to

the vulnerability of a lethal weapon in his comrade's hands for

the privilege of the distinction. As the saying goes, if it

weren't for the honor of the thing ...!

Not only was there a great variation in uniformity in Vietnam,

but more than thirty years after the war, new unauthorized

insignia from various small units continues to emerge. Whenever

possible, these badges were worn on jacket pockets in solidarity,

but if commanders objected to the paramilitary gang

theme such illegal displays propounded, then these patches

migrated inside the shirt or hat. Such livery was often crudely

handmade in very small quantity at a local tailor's shop for a

nominal fee, but they served the purpose of melding a disparate

group into a cohesive element. These unauthorized insignia

represent a perspective on the historical experience, and due to

their scarcity, such emblems have become very collectible at

astonishing prices. This rarity has generated fraudulent and

exploitative imitation, but everything desirable is copied in one

form or another, from speech and conduct to activity and

ornament.

One historian has interpreted the Vietnam War by tabulating the

tokens and mementos which set this event apart from others. He

itemized the plaques and chits, the challenge-coins and souvenir

militaria, to create a discrete image that juxtaposes the

headline accounts. His account didn't tell the conventional story

of the war, but then the typical timetable tends to omit the

minor details which constitute the only point of reference that

any veteran retains. Not only was the Vietnam experience

strategically inconsistent (as one pundit has said: not ten

years, but one year repeated ten times!), but it was

personally incoherent for troops who could not reconcile the

impractical rules of engagement with the lavish

nation-building campaign; so their own private

war became the only substantive reality. A couple of other

historians have documented the war by the things they

carried, from external-frame rucksacks and jungle hammocks

to filter-necked canteens and whisper-microphone radios. Because

the average person lacks the experience of combat, and often

doesn't understand any of the intangibles, most people

concentrate on the objects associated with war

... whether as icons or as symbols. A spouse is supposed to

extrapolate an entire gestalt of an alien past when shown a

collection of tattered photographs, a lapel rosette, a necklace

bearing identity tags, a P-38 can-opener, some tarnished

brass shell-casings, some rusty grenade pull-rings, an emblematic

mug, a stained plastic spoon, and a pair of handcarved

chopsticks. The bereaved family is presented a triangular-folded

flag and a box of decorations in exchange for the loss of their

loved one ... who will never return to recount tales or explain

deeds, who will live only in continuing memory, and who will

embody these otherwise meaningless objects.

Sometimes objects are all we have of someone or someplace, to

remind us of the way things truly were, and of how we've changed.

These mundane objects get imbued with sacred significance, and

often acquire fetishistic powers ... that lucky pocket knife not

only sustained life in peril, but enabled a career, so it must

never get lost! An adolescent cannot imagine that any of us was

once young and vigorous, with distinctive markings apart from

checkered age, and the next generation will be unable to picture

us as vital warriors, so this detritus of antiques or

agglomeration of disparate objects is just a curiosity without

context. As the value of allegiance and the meaning of intent

changes, those associated objects are often derogated,

diminished, and dismissed. Their meaning is not intrinsic, but

extrinsically permeated by the marvelous acts of ordinary men

in uncommon situations. When our most private thoughts

cannot be otherwise expressed and our intense feelings cannot be

adequately represented, we invest symbols with this surpassing

significance; and we remind ourselves of their valid importance

by revisiting such inviolate touchstones whenever

necessary.

For those who've endured the crucible of combat, a gallows

humor pervades most events and taints most objects. A noble

lineage or proud heritage is ironically reduced to Poison

Ivy or Psychedelic Cookie, to Dancing Pony

or Burning Worm, to Electric Strawberry or

Electric Butter Knife, to Ace of Diamonds or

Lonely Hearts, to Leaning Shithouse or

Puking Buzzards as irreverent unit designations, without

any particular loss of esteem. The winter soldiers of

Vietnam extended the official psy-op propaganda leaflet program

by privately printing their own unit death cards to be

left on the enemy corpses as a warning and affront. Novelty cards

of exaggerated prowess and ridiculous testimony, purporting to

perform valuable services, such as taming tigers and deflowering

virgins, were widely personalized. Certificates for members of

the Mushroom Club, who were kept in the dark and fed

on horse shit, and the Loyal Order of the Aching Foot

and Exhausted Rope (LOAFER), who were to be hung by a snap-link

until tired or retired, were also circulated. The

mountaineering snap-link, that's widely used in rappelling, is

properly called a carabiner, which derives from a hook

used to attach a carbine to the bandoleer. For many soldiers, a

carabiner signifies their competence and proficiency in military

skill crafts. And upon completion of one's tour, some compatriot

would bribe a clerk into typing a precautionary DEROS notice

to be sent as a warning to an unsuspecting family, saying that a

thoroughly demoralized and uncivilized person, at risk of losing

his native language to pidgin, and needing to again be house-trained, would shortly return to their exotic world ... the

land of the big PX!

Vietnam was the time when one of the oblong metal identification

tags was displaced down to the grunt's foot to help relate

dismembered body parts. These days, outdoorsmen have a special

two-hole dog-tag for lacing flat against their ergonomic

waffle-stompers as an emergency medical or

identification label. Vietnam was the time when real men

unapologetically wore earrings, as criminal bands or aberrant

cliques have long done. The practice originated with

reconnaissance teams, such as Project Omega, which commissioned

custom Greek-letter jewelry for its teammates, and the fashion

eventually spread to other units. This practice reminded me of

the novice starship trooper that Robert A. Heinlein

portrayed as asking where to buy those attractive skull earrings,

and being told that they weren't for sale ... they had to

be earned! Now, of course, in our devalued hyperbolic

society, everything is for sale, including fake

memorabilia, phony documentation, and replica medals. A little

authenticity goes a long way.

|

Montagnard bracelets flanked

by POW/MIA and KIA

bracelets

|

|

Vietnam was also the time when bracelets became popular. World

War One moved the pocket watch onto the wrist for practicality,

and World War Two popularized the loose-link sweetheart

or slave bracelet as a personal connection, but Vietnam

brought everything to a productive art form. Designer watches and

watch-bands became status symbols, and a few soldiers regarded

their solid-gold link-bracelets as convertible cash or

portable wealth. Vietnam was the time when helicopter

crewmen would cannibalize a cable conversion into a unique wrist-band that forged a link with all other prop-heads.

Advisors to indigenous partisans were often assimilated into the

particular subculture in their area of operations. The symbol of

this adoption was the unique circlet (kong), bearing the

identifying tribe's stylized markings, handcrafted for

intrasocial rites. These mountain peoples would rework available

metals, so the bracelets not only varied between tribes, but

within a tribe from year to year ... sometimes brass or copper,

sometimes tin or aluminum. This loop-bracelet was presented in a

solemn animistic ceremony of public affirmation. Several advisors

thought enough of their filial bonding to adopt their own

stateside wives into the tribe by uttering mutual vows and

exchanging bracelets for wedding bands. As time passed, and

events changed circumstances, the Montagnard refugees needed a

livelihood, so beautiful bronze and sterling silver reproductions

were offered commercially, with a pamphlet explaining the

significance of the object, the meaning of the symbolic signs,

and the plight of these dislocated peoples. These handsome

facsimiles weren't made in the old way, and their quality is much

improved by the marketing, but they lack the power

(yang) that gave them meaning, so these artifacts have

become just another trinket. This loss of spirit begins the

decline of heritage for a besieged ethnic group. There will

always be a profound difference between spending blood and

wasting money.

Vietnam was also the time of another unique bracelet. What most

people don't know about that war is that it remained popular with

the American public until the piecemeal troop withdrawals, and

even then, most people blamed politicians more than soldiers. It

was possible in those chaotic times to find a peace

demonstrator or a war protestor wearing a

Prisoner-Of-War / Missing-In-Action bracelet. Unlike the controversial peace

symbol, which often implied crypto-abetment of the enemy,

the POW/MIA bracelet was never a litmus-test of loyalty, but it was a declaration of solidarity. As

a result of some regulatory complications, the families of

captured or missing servicemen were suffering isolation,

alienation, and financial distresses. A coalition was formed to

assist these families, with non-profit funds raised by the sale

of POW/MIA bracelets. Being originally a plain

aluminum cuff, engraved with the vital statistics of one of the

hundreds of men who were unaccounted, the bracelet evolved into

red-enamel, copper, brass, and stainless-steel versions. In that

halcyon age of naive idealism, the purchasers pledged to wear

their distinctive bracelet until the name it bore was accounted

for, or the person returned. Subsequent to the accord protocols,

the remaining prisoners were released from North Vietnam, and

many persons mailed their bracelets to the repatriated servicemen

to demonstrate the faithful keeping of traditional virtues. The

POW/MIA bracelet became so popular that it

spawned a blue-enamel version for the thousands of Korean War

servicemen who still remain unaccounted. There is no World War

Two version, not only because it was the good war that

was decisively won, but because the MIA count is

remarkably high ... Operation Torch alone, when the Allies first

invaded Axis territory, had more MIAs than

either Korea or Vietnam. A black-enamel KIA

version exists for the remembrance of anyone Killed-In-Action.

After the return of American prisoners and the end of the Second

Indochina War, the POW/MIA bracelets became

politicized because one faction wanted a progressive

normalization with Southeast Asia, and another faction of

true believers sought complete accountability in a

region that lost millions of Asian dead to privation, famine,

disease, and violence. Allegations of bad faith and

cover-up plagued every expeditious negotiation, and

cohesive fusion devolved into ulterior convictions. The question

of complicity or conspiracy was perceived, rightly or wrongly, as

one more divisive issue in the endless Vietnam quagmire; and the

bracelets became tainted. There was a brief half-hearted effort

to revive them for the Persian Gulf War, but yellow

ribbons, which have a pioneer legacy unbeknownst by many

adherents, captured the popular mood as declarative

favors ... those tokens of loyalty displayed by knights

that later evolved into award ribbons and decorative medallions.

The War on Terror has spawned a sand- or khaki-colored cuff known

as a deployment bracelet, which bears the personal

particulars of a loved one serving in the Mid-East theater, in

the Afghanistan or Iraq war zones.

A friend of mine, who's also a multiple-tour advisor veteran,

recently made a mid-life career change into teaching. Although

hired to instruct math and coach wrestling, he's found himself

tutoring his colleagues in political science and his pupils in

civics. Not only have the students been curious about his

bracelet, but so has the faculty. He's transitioned from polite

explanations to defensive apologia. For the staff, the issue

escalates from the unobtrusive bracelet to the ethics of war, in

general, and the immorality of the Vietnam conflict, in

particular. He finds himself teaching history to his misinformed

peers, attempting to dispel dogmatic myths and revisionistic

stereotypes, without condoning the war's flagrant errors. For the

students, the issue de-escalates from a symbolic object to a

deviant affectation, in particular, and an abnormal trend, in

general. He finds his attempts to socialize and acculturate his

charges is somewhat compromised by their perception of his

difference. His commitment to a principle is judged

cool, and his belief that those lost in war's maelstrom

should be remembered is pronounced neat. Because they

lack the aptitude and insight, he cannot inform them that

the world is diminished by the loss of good and decent

people. They do not understand that the name on this

simple bracelet should be a name in some telephone book, a name

on a work schedule, a name on a tax-roll, and, most of all, a

name on a gift list with other relatives and friends.

When dressing to go out for meetings or other occasions, it has

been my habit to emplace two yard bracelets and three

KIA bracelets on my left wrist ... just below my

patriotic tattoo. I'm not as caring and considerate as my teacher

friend, so I'm indifferent to anyone else's understanding, and

I'm resigned to the inevitability of an inaccurate history. One

of the ugly truths about mind-sets is that some people actually

want to be brain-washed, so their skepticism only

reinforces their prejudiced conclusions. What's important is that

I sustain a cogent integrity. It's like the difference between

someone doing something for credit or a reward, and someone just

getting it done because it's necessary ... regardless of whether

it's public altruism or private worship, whether it's public

civility or private abstinence. The objective is that I

remain faithful, so it's immaterial if someone

thinks that my ostentatious display of gaudy jewelry is garish,

or thinks my exaggerated indulgence is grandiose exhibitionism.

Like the mendicant accused of making a virtue of

poverty, I cannot prevent fallacious deductions. Because the

wearing of the bracelets is not about

me, and I do not benefit from

its ancillary implications, I've attempted to devise a way of

destigmatizing the act.

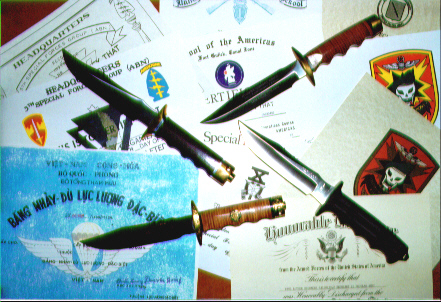

|

excellent post-war versions

of the SOG bowie

|

|

Since Montagnard bracelets can be mistaken for bangle adornment,

and since POW/MIA bracelets are imbued with a

mystique, the solution I devised involved changing the form

to restore the function. While the yard bracelets

implied the advisory role, they didn't identify the deceased

advisor confreres. And while the KIA bracelets

specified the casualties, they didn't entail the advisory

experience. I needed an object that was common to both, and I

settled upon the renown (and even notorious) knife commonly known

as the SOG bowie. This unusual knife was

originally designed as an issue item for special operations

personnel, but was so poorly made that its distribution was

refused by team members, who preferred the higher quality but

equally inexpensive Pilot's Survival knife.

Despite the fact that the so-called SOG bowie

would rust before your eyes, would break at the first resistance,

would lose its leather haft to torrid rot before the end of the

patrol, and was duller than elephant grass, it had considerable

cachet ... derived from the prestige of the stipulated

units. Unlike the utilitarian banana bolo or the

effective Mark-2 (generic KaBar)

fighting knife, the SOG bowie, which was also

known as the sexy Japanese Randall[†] was not in

operational demand ... after all, a bamboo punji stake

would make a better knife ... so it naturally became a

presentation item! This was also the fate of the equally

notorious Fairbairn/Sykes commando dagger during World

War Two, which also makes a much better trophy than fighter. The

honor graduates from the in-country training centers operated by

special forcemen, such as the MACV Recondo School, were presented

with this prized knife ... as many others were at the completion

of their assigned tours of duty. Since all of these men worked

within the counterpart system, this object would satisfy

both symbolic requirements. After the war, this

clipped-back bowie design proliferated, and numerous

examples of excellent quality, both custom and factory versions,

now exist. However, a knife, whatever its features, can send some

unwanted messages and is most certainly not a bracelet.

I contacted a friend, who's a professional knifemaker, to inquire

about the possibility of commissioning a custom cuff-bracelet in

the profile of the SOG bowie. We discussed the

options and problems, and settled on extremely thin titanium-sheet stock that would be cut, engraved, and shaped. The profile

had to be slightly blunted or blurred to prevent inadvertent

injury, but dramatic enough to be readily recognizable. The knife

bracelet was reverse-side marked in keeping with the sinister

heraldic representation of the unit's clandestine mission. I

declined the option of anodizing the bracelet a deep dark gray,

which would've resembled the standard black enamel, and kept it

as unpolished raw metal. Since I'd already rationalized the

over-kill situation of excessive display, I decided to

put all the vital statistics from three KIA

bracelets onto only one knife bracelet. At a distance,

the new bracelet might appear to be a watch-band ... nearer, a

piece of etched jewelry, and up-close, a strange totem. There

would be no more knee-jerk reactions to politically

incorrect stimuli, because this object was unassimilated into

anyone's litany. They would either have to figure it out for

themselves, and live with the consequences of their inference, or

ask an impolite and ignorant question ... to which I wouldn't

deign an informative response. So far, no one's done either, and

I've been left alone to keep the faith.

|

|

|

One of the things that has been repeatedly learned throughout

history, and seemingly must be eternally re-learned, is that

despite all of our differences, we have more in common with each

other than not. The proximity melting-pot may never

homogenize us into indistinguishable clones, but society

certainly evolves a hybridized admixture. Such heterogeneity may

create unusual composites, such as the respect which converts

former adversaries into allies, or the spirituality that bridges

stratifications, but they only prove our essential commonality

anew. The symbolic objects which serve to define us as separate

and different also prove our connectivity. As unique cells work

together in bodily processes, so people find some level of

cooperation and coordination essential for body-politic or

environmental processes. There is nothing wrong with group

affinity, as long as everyone remembers their greater context and

complete unity. There is no good reason to fill the canton of our

national ensign with so many separate stars, except for the

inexorable fact that we are a whole comprised of numerous

indivisible parts. And least we become hostages to inconstancy,

these simple objects of allegiance remind us to keep

faith with every precious thing.

[†] : the origin of

the so-called SOG bowie was generally unknown

for many years, due to rigorous obfuscation and classification

criteria, which obscurity spawned a plethora of speculative

fiction. In spite of obvious qualitative defects, the knife was

often purportedly made (allegedly under top-secret contract) by

the world-famous knife-innovator W.D. Bo

Randall at his small forging manufactory for benchmade

cutlery. Despite numerous denials of association or

credit for the SOG bowie, and despite

the long history of excellent military productions, from the

model 1 All-Purpose Fighter and model 2

Stiletto to the model 14 Attack

and model 17 Astro, the rumor persisted. Best

evidence indicates that the SOG bowie was

produced under contract by the Counter Insurgency Support

Office (CISO, MACSOG-40) on Okinawa, as a nominal

logistical unit operated under the U.S. Army Pacific command,

which was acquired from the Central Intelligence Agency during

Operation Switchback in 1964.

[return to text]

by Paul Brubaker

... who is retired from the U.S. Army, has since been a

counselor, artisan, and writer, with numerous essays published in

chapbooks and magazines.

|