Oliver Cromwell, Warts and All

The only interruption in the long history of the English Monarchy

occurred in the years 1649-1660. The reasons were economic,

social, political, and religious. While some historians of recent

bent have downplayed the part of religion in the struggle –

probably because they themselves are irreligious – its

significance cannot be denied. One group in particular, who saw

the happenings here on earth as merely a prelude to the much

greater glory of the hereafter were the Puritans, so

named not by themselves but by their enemies, who saw it as a

joke. A more correct name would have been Fundamentalist

but the name of Puritan has stood for centuries.

They also believed that God did not choose just anyone to inherit

His Kingdom, but rather those who made it their life's work to

try and understand the goodness of God. Central to this belief

was the tenet that humankind needed no help from bishops or

priests to help them reach their goal, but that any man or woman

had direct access to God. This could be described as dogmatism

but was in truth no more dogmatic then the other prominent faiths

of their day. One only has to read the words of H.L. Mencken, who

said that Puritans are people who are worried that somewhere,

somebody, might be having a good time, to know that even

today the Puritans are a much misunderstood group.

|

Oliver Cromwell

in battle dress

|

|

One of these Puritans was a man named Oliver Cromwell, a

man so great, he would lead the fight in removing the King of

England from his throne – and remove the King's head as

well – would take the lead in establishing an English

republic, then actually rule that republic for five years with

the title of Lord Protector.

Oliver Cromwell was born 25 April 1599, to not rich but not poor

parents who lived in the community of Huntington. They might be

described today as middle class, and due to their societal

status, Cromwell was entitled to wear the title of

gentleman. He enrolled in Cambridge at age seventeen but

was forced to drop out after fourteen months when his father

died. He quickly assumed his role as the man of the

house and would remain solicitous of his mother and his

several sisters for the remainder of his life. While at Cambridge

he established a reputation as being better at sports than books,

and as one who temporarily cast off some of his strict

upbringing, by indulging in a certain amount of debauchery, at

least by the standards of seventeenth century England. His

debauched life continued for a time after his assumption as the

head of his family and it was said that he became the terror of

the local alehouses. In essence, he was not living the Godly

life. This too would change, when his mother, in no doubt an

attempt to reign in his youthful indiscretions, sent him to

London to study law (among other things) at the famous Inns of

The Court, a training facility previously attended by his father,

his grandfather and two of his uncles. It was while at the Inns

that Cromwell became a studier of men, rather than books, and

preferred the practical, as opposed to the theoretical, traits

that would serve him well in the years to come. On 22 August

1620, Cromwell married Elizabeth Bourchier, daughter of a City

magnate. He and Elizabeth's families had known each other for

many years. Trivial pursuits would no longer be part of

Cromwell's life. The marriage would be one of love and devotion,

despite the fact that the husband would be absent for long

periods. It was about this time he encountered Jesus Christ and

joined the sect known as Puritans.

It was an event that happened in 1625, the death of King James I,

that began Oliver Cromwell's ascent to immortality and would make

him one of the most loved and most hated names in all of English

history.

Charles the First, King of England, Ireland and Scotland assumed

his throne at the age of twenty four. He would make many

mistakes. To Protestant England, his taking of a French princess,

who was also Catholic, as his Queen was one of the most severe,

especially to those who had and innate fear of popery.

By 1628, Charles had England embroiled in an expensive war with

Spain and was quarreling with France. The English Parliament,

unlike our United States congress, could only be called into

session by the King, usually when the King got himself in a hot

spot and didn't know how to extricate himself. Young Oliver

Cromwell was a Burgess from the town of Huntington when Charles

called his third meeting with Parliament.

Up until this time, the King was regarded as the undisputed ruler

and everyone else, including Parliament served at his behest. The

cry – there is only one King – was said to

have a mystical quality about it. Charles the First

thought so too, since he was quick to remind doubters that he

ruled by divine right. But many in England, especially

in Parliament, doubted this and were becoming more open in their

opinions. Oliver Cromwell was one of the doubters and was

thoroughly on board with his Puritan brothers and

sisters, who believed that only Jesus Christ ruled by divine

right.

Another bone of contention was Charles' insistence that the King

had the right to make laws without the consent of Parliament. The

King believed that it had always been this way while Parliament

disagreed. This created a situation, which would have been rather

amusing if it weren't so dangerous, that had both sides yearning

for the good old days. Young Oliver Cromwell sided with

those who believed the king had too much power, and with his

Puritanism now in full bloom, he was quick to indulge in

thoughts that could be considered treasonous – that only

God Almighty ruled by divine right. And the more he thought and

the more he prayed the more he saw himself as God's

instrument. Only three months later, Cromwell and his

associates in Parliament made their feelings known in The

Petition of Rights. Charles Stuart accepted the petition

while declaring that he had to answer only to God. Yet

could God be on both sides in the debate?

Of all the issues, the more serious was that of religion and the

threat of Popery. If the king did not have to secure the

advice of Parliament, could not his queen press for the advent of

Catholicism as the official religion of England? And yet the

major religious argument did not concern Catholicism versus

Protestantism, but rather The Church of England versus

Puritanism.

The declaration of the Archbishop of Laud that Puritan

tendencies must be checked, that the Church of England would

decide the proper mode of worship, led to an establishment of

The Committee on Religion of which Oliver Cromwell was

an outspoken member. It's difficult to believe that even today,

some will declare that the issue of religion did not play a

prominent part in the three Civil Wars to follow. Surely it was

the motive for Oliver Cromwell's participation, and it was during

the Civil Wars that Cromwell would discover his greatest talent

– that of soldier.

The decade of the 1630's was a difficult one for England and

particularly for Charles Stuart. He had to deal with rebellions

in Ireland and Scotland, and the Irish rebellion caused much

consternation in Protestant England when reports of a massacre of

Irish Protestants by Irish Catholics were rampant –

historians now agree that the so called massacre was

greatly exaggerated. The intransigence of Stuart when it came to

negotiations with Parliament concerning how power should be

divided, and the persecution of influential Puritans by

the Church of England caused even more furor. The more Charles

tried to hang on to his power, the more devious and disingenuous

he became. When he dissolved what came to be the long

parliament of 1640, the stage was set for arguments that

could not be negotiated with words, but to be settled by canon,

rifle, sword and pike. By the time it was over, the monarchy

would be no more and Charles would lose his throne and his head;

and middle class Oliver Cromwell would be the most powerful man

in England.

The English Civil Wars were not between the haves and

have nots. In other words it was not a class

war, as some historians have insisted. Indeed, like the

American Civil War, communities, families, and religions were

divided. The two sides were supposedly split between Royalists

and Parliamentarians; yet many titled men wanted to be rid of

Charles Stuart and fought with the Parliamentarians' side, while

some of the poorer sections of the country remained staunchly in

favor of the King. But there was one group that was not split.

The Puritans who rode into battle with Oliver Cromwell

were called Roundheads because of their pageboy

haircuts; and they had no doubt what they were fighting for

– the right to worship God as they saw fit. Their commander

would come to be known as Ironsides because of his

fierceness in battle.

Oliver Cromwell had no formal military training. What he did have

was the courage of a fatalist – I will fall if God

wills it – an innate talent for organization, supply,

and the ability to spot weakness in the enemy defense. He would

become the nemesis of Prince Rupert, the nephew of King Charles,

who had significant battle experience. The Battle of Edge Hill on

23 October 1642 would also show that Cromwell learned something

from every battle, in this instance, how to get the most out of a

troop of cavalry.

Although he arrived at the Battle of Edge Hill only in the later

stages; through his keen observation he saw that Rupert, despite

his military experience, did not have a disciplined troop, and

that his Cavaliers after making a charge were so spread out that

they then lost all effectiveness. The bee stings only

once observed Cromwell. He knew he'd already trained his

Roundheads to quickly reform after a charge and get ready for

another. He also knew his cavalry was superior because he

promoted men on merit rather than station. And there was the

matter of spirit, something sadly lacking at Edge Hill,

which ended with much blood being shed but little accomplished.

He had men of spirit and would get more godly men who knew this

was a religious war. The King had told his men they'd be

fighting Baptists, Atheists, and the like and did not

the Parliament speak of The King and his popish army?

Thus he would take care to get Godly, religious men –

freeholders and freeholders sons – who saw this war as a

matter of conscience. Let others get soldiers who joined to

plunder, and he and his good men would defeat them in battle.

When the Earl of Manchester, Cromwell's superior for a time,

inspected Cromwell's officers and men he was amazed at the number

who considered themselves Godly. Their commander would

permit no criticism of his soldiers – better to have a few

honest men then a number of dishonest ones. One observer said

that Cromwell's men never ran once before an enemy, they

would as one stand firmly and charge desperately. In time,

those who laughed at the Roundheads of Ironsides would

come to fear these commoners who never retreated.

Cromwell and his Roundheads had their first baptism of

fire on 13 May 1643 at the town of Grantham, and were

victorious in their first independent battle. As we had stood

a little above musket shot, the one body from the other, and the

dragooneers having fired on both sides for an hour or more, they

not advancing, we decided to charge, and advancing the body after

many shots on both sides, came on with our troop on a pretty

round trot, they standing firm to receive us, and our men

charging fiercely upon them, by God's providence, they were

immediately routed and ran away. Though this was just a

skirmish, it proved Cromwell could win when he was the highest

ranking officer on the field. It did not go unnoticed by his

superiors, especially Lord Fairfax, Supreme Commander of the

Parliamentary Army.

By the end of the campaign of 1643, Oliver Cromwell had

established himself as second only to Thomas Fairfax in skill as

a military commander. Those who doubted the fighting ability of

the novice military commander by now had all their doubts

dispelled.

One reason King Charles believed his Royalist army would win the

war was because of the many divisions, mostly centered on

religion between the various Parliamentary factions. He was wrong

about the war but right about the divisions.

On 18 January 1644, twenty thousand Scotsmen, Presbyterians all,

under the command of Alexander Leslie, marched into England, come

to join the fight against Charles Stuart. But their allegiance

had come at a high price. To begin, the payment of 100,000

pounds; and then the real fly in the ointment:

Parliaments acceptance of the Solemn League and

Covenant, which was essentially an agreement stating that

once the war was won, and the Church of England, with its Bishops

removed, Presbyterianism would become the dominant religion of

England. Obviously this was a red flag to Oliver

Cromwell, now a Lieutenant General of increasing influence in the

Parliamentarian army. For one, he didn't think the help of the

Scots was needed, and secondly, he felt that the war was being

fought for religious freedom and would never submit to any

agreement that opposed it. He finally signed the agreement

sixteen months later after being assured that existing faiths

would be left untouched.

Cromwell would next lock horns with Major General

Laurence Crawford, a professional soldier from Scotland who

apparently looked askance at this upstart amateur, who was

nothing but a farmer. Things came to a head when Crawford

arrested one of Cromwell's men, a Baptist who had not signed the

Covenant. Cromwell defended the Baptist: Sir, the

state in choosing men to serve them, takes no notice of their

opinions if they be willing to faithfully serve them, that

satisfies. I advised you formerly to bear with men of different

minds of yourself; If you had done it when I advised you to do

it, I think you would not have so many stumbling blocks in your

way. It may be you judge otherwise, but I tell you my mind.

From this we can take that in an era of closed minds, Cromwell's

was at least part way open.

|

|

|

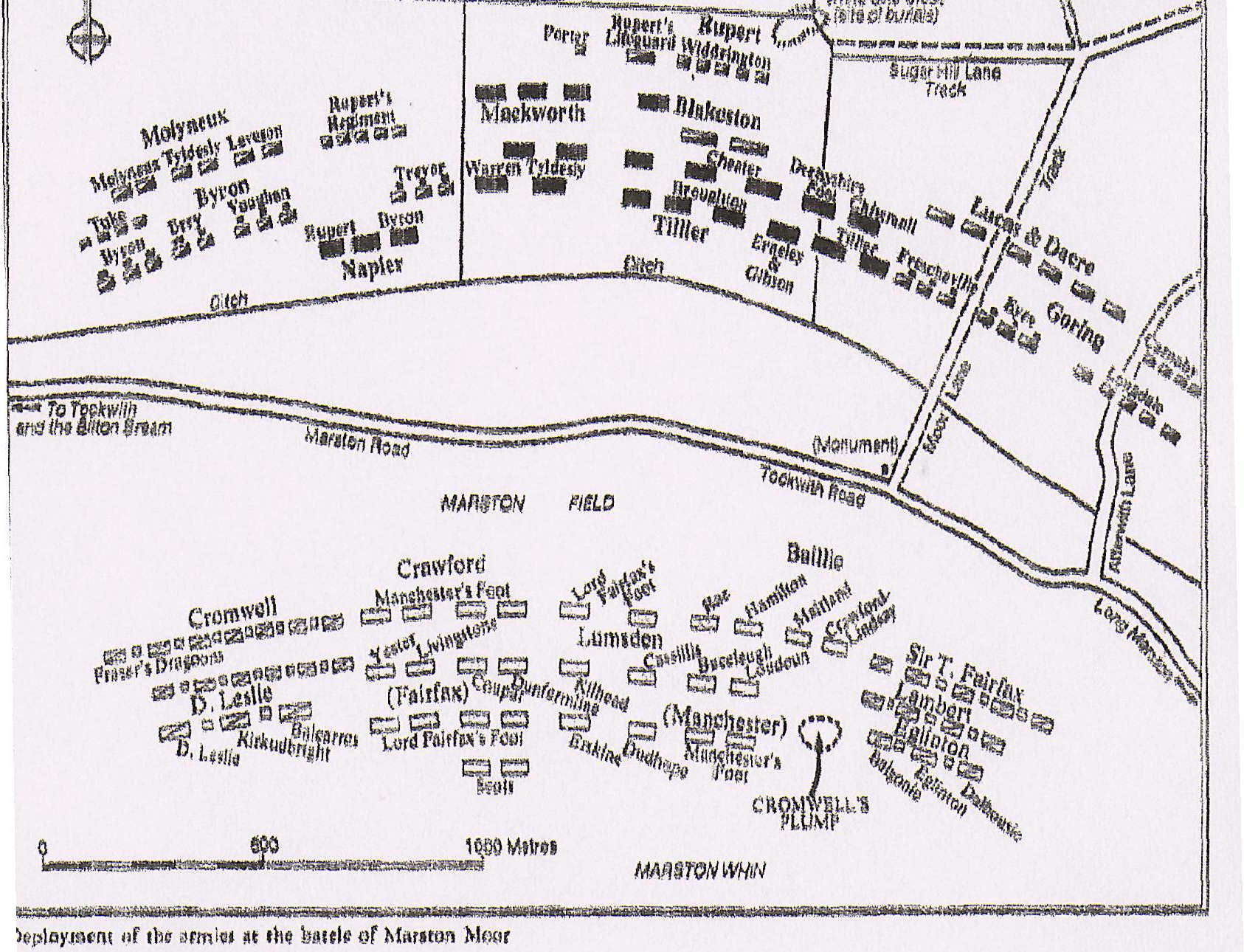

The Battle of Marston Moor on 2 July 1644, was the biggest ever

fought on English soil, with eighteen thousand Royalists facing

off against twenty-two thousand Parliamentary troops, and

Lieutenant General Oliver Cromwell and his twenty-five hundred

cavalrymen would be right in the thick of it. The battle lines

stretched for two and a half miles. Since it was late in the day

by the time both lines formed, Royalist commander Prince Rupert

decided there would be no battle until the morrow; so he sat down

to supper. But the army of Parliament had decided no such thing.

A surprise attack was in order. A storm was gathering, rain and

hail falling as the Parliamentary line started moving forward on

a broad front, with Cromwell's cavalry leading the way, not at a

gallop, but a controlled trot. According to one chaplain

observing the attack, the army's various components looked

like unto so many thick clouds, and it was Cromwell's

cavalry which charged most ferociously, scattering their

opponents like leaves in the wind.

But on another part of the field, Fairfax was having trouble, at

one time finding himself surrounded by Cavaliers. When Rupert

heard the firing of the charge he sprang into action. Soon,

Cromwell found himself surrounded by Cavalier cavalry and only

the assistance of Leslie's Scots saved the day.

It was at this point that Cromwell, due to a neck wound, had to

retire from the field, and soon the Parliament troops were on the

defensive as Rupert made a successful counter charge. The battle

raged back and forth with neither side giving ground. Then

suddenly Cromwell was back on the field! Leading another charge,

scattering Rupert's men and sending them flying along by Wilstrop

road as fast and as thick as could be. But here again, Cromwell's

discipline took over. Let Rupert run, he would reform his troop

and attack other bodies not yet beaten.

On another part of the field, things were not as rosey for the

Parliamentarian army. Fairfax had managed to get back to his own

troops only to find that some of his officers had deserted the

field while other Scotsman were fighting for their lives. Things

looked bleak and defeat was near.

But wait! A cry was heard! Lord of Hosts to the attack!

And here came Cromwell, exhorting his troopers and scattering the

Royalists who didn't stop running until they'd reached the city

of York. The victory had been won and the victorious Parliament

army said a psalm of Thanksgiving and lay down to sleep on the

blood stained field, where upwards of four thousand Royal army

soldiers lay dead.

The allied Parliamentary army had lost only three hundred killed,

but one of those was the son of Cromwell's brother in law.

Cromwell had already lost his son Oliver in a previous

engagement, so understood the pain. Cromwell wrote: He was an

exceedingly loved young man, your precious child full of glory,

to know sin nor sorrow no more.

Battlefields were a horrible place in the day of the cannonball

and pike, with few doctors and no field hospitals. And in the

battles of a Civil War it can be certainly said that the country

suffers from the deaths of either side.

After the victory of Marston Moor, Cromwell set about convincing

his comrades in the military and the House of Commons of the

necessity of improving discipline and the fighting skill of the

army, and also of the necessity (this was a harder fight) of not

only defeating Charles Stuart on the battlefield, but of getting

rid of the monarchy altogether. The outgrowth of his argument

concerning the army was the creation of the New Model

Army, which, though many had doubts about, would insure the

victory to come. It was a tough fight mainly because of the

green eyed monster that afflicted some of the

professional soldiers who resented Cromwell – the farmer

– and who therefore had a tough time admitting he was

right.

But, as already mentioned, it was much more difficult to convince

both civilian and military that disposing of King Charles was

good for England. England had always had a King, and Stuart's

intransigence when it came to letting go of any of his power

notwithstanding, there were few who didn't think something could

be worked out. Most of Cromwell's contemporaries wanted to defeat

the King in battle yet keep him on the throne. This was a source

of great frustration to Cromwell, and one officer in particular

was driving him to distraction.

The Earl of Manchester since the beginning had seemed to fight a

half hearted war, which was bewildering to everyone, especially

the Scots. At one meeting, after the Battle of Marston Moor,

Manchester revealed his ambivalence: If we beat the King

ninety-nine times, he would still be King, and his posterity, and

we his subjects still, cried Manchester, but if he beat

us but once, we shall be hanged and our posterity undone.

Extremely irritated, Cromwell replied – My Lord if this

be so, why did we take up arms at first? No doubt part of

Cromwell's frustration was due to the fact that some who had been

fighting nobly by his side thought as Manchester. But Cromwell's

power was growing and the affair was ended with Manchester giving

up his command, and the New Model Army taking the field

in May of 1645, and none too soon.

Despite the great victory of Marston Moor, Charles Stuart was not

even close to throwing in the towel. Indeed a great

victory by General Montrose in Scotland and the promise of Irish

Catholic soldiers on the way gave the King renewed hope. This

told Cromwell and the Parliamentarians that they must take the

field.

Cromwell continued his brilliance on the battlefield. In a series

of skirmishes, he beat the King's soldiers in every way possible.

In what was supposed to be a battle at Bletchington house, his

opponent retired from the field, leaving him with a goodly supply

of ammunition, horses, and muskets. He was especially pleased

with the horses. Some have always insisted that what made

Cromwell such a great cavalry leader was his knowledge and love

of horses. He always knew when his horses could go no further. He

was ready to fight the final big battle of what came to be known

as the First Civil War.

Some historians say the Battle of Naseby is incorrectly named,

that it should have been called the Battle of Broadmoor.

It's generally believed that fifteen thousand Parliamentarian

soldiers faced twelve thousand Royalists. No matter the number,

the Royalists put up a very poor fight, since the allies claim to

have captured five thousand prisoners while losing only two

hundred of their own men.

The battle began at eight in the morning on the 14th of June

1645, and as always, Oliver Cromwell played a key part. It was

Cromwell who suggested to Lord Fairfax , as they faced the

Royalists aligned on a mile long ridge to their front that he

retreat only slightly so as to lure Prince Rupert into charging

across a marshy bog unsuited for cavalry. One wonders why Rupert

didn't know about the bog, but Royal scouting during the Civil

Wars was generally bad, and Rupert rarely trusted it. Add to this

that Charles Stuart had overall command of the Royalist army, and

in fact had the habit of overruling his nephew, and Rupert was

becoming more unsure about his decisions.

Cromwell however, was confident and full of fight –

riding about my business, I could not but smile out to God in

praise, is assurance of victory. The battle lasted three

hours and once again was decided by Cromwell and his men, who

even if they were checked or beaten, would quickly reform and

charge again; while Prince Rupert's men would charge once

and then never again.

One serious consequence of the Battle of Naseby, and one King

Charles tried to laugh off, was the finding of a cabinet of

letters written to his wife in France, who was trying to raise

troops for the Royalist cause. With the publication of the

letters, many people who thought he should be able to keep his

throne now realized that treason had been committed, and Charles

Stuart must go. There was now only one large Royalist force left

in England, that of the brave but erratic General Goring, and

Fairfax set out to engage him.

Goring was cornered at the Battle of Longport, and a series of

cavalry charges, the last by Cromwell, turned the tide, and

Goring surrendered. Prince Rupert on hearing the news, advised

his uncle, King Charles, to get what terms he could. But Charles

Stuart, stubborn to the end, accused Rupert of treason and fled

to Wales, where he would try to raise another army. Charles may

have been the only one not to realize that his fleeing days were

about to end.

In January 1646, Cromwell returned to Westminster to report to

the House of Commons and be thanked. His star was shining

brighter than ever as defeated Royalists left the House of

Commons and their seats were taken by Cromwell's friends and

fellow officers.

With the First Civil War now over, Charles Stuart became a

prisoner of the Covenanter Scots who had hopes that he

would accept Presbyterianism as the official religion of England,

and if so, he could save his throne. Also at this time, Charles

yielded to the pleas of his wife, Queen Henrietta, to get their

son, Charles the Second, the Prince of Wales, out of England and

into France with her. No doubt Stuart, after losing the First

Civil War, saw exploiting the divisions between the Scots and the

Puritans as his only chance.

It was a time of great turmoil in England, with many switching

from the Puritans back to the Royalists, particularly

since some of the Puritans, in their zeal, began taking

the fun out of the lives of the average Englishman. Christmas

celebrations were forbidden, plays and other entertainments were

canceled. Although Oliver Cromwell was not directly involved in

these privations, it was he, as the biggest Puritan

name, who was blamed. The victorious Parliamentarian army was

also becoming a nuisance to the citizenry – particularly

the commoners who didn't care which side won – who raised

petitions asking for its disbandment.

All of this was playing into the hands of Charles Stuart, who was

convinced that, given enough time, he would be welcomed back

without having given up anything. He still had no understanding

of what had happened and that even if he were permitted to live,

he would never again have the power of previous days. The more

devious and stubborn he became, the closer he got to the chopping

block.

Meanwhile, a rift occurred between Parliament and the army. The

soldiers had no intention of disbanding, because their pay was in

arrears, and no compensation had been paid to the widows and

orphans of their comrades. They also refused Parliament's order

to go to Ireland, and put down the Irish Catholic uprising.

The disagreement between Parliament and the army warmed the heart

of King Charles, who had been waiting for just such a situation

to tell Parliament, who in addition to the Scots, had laid down

certain terms by which Stuart could return to power, that he

agreed in principle to their terms. But Charles had overstepped

again. When the army heard what was planned, they rushed Holmby

House, where Charles was being held, and seized him. Stuart was

now under the protection of the army, which meant no

protection.

But Stuart continued to play both ends against the

middle, promising Cromwell and the Puritans that

all sects would be protected, and also promising the Scots that

he would accept Presbyterianism and suppress all the sects if

they would restore him to his throne. The result of this was to

heal the rift between Parliament and the army, which until now

had seemed unhealable. A vote was taken to stop all negotiations

with Charles Stuart. The healing of the rift between the Army and

Parliament came just in time. They would need to be united if

they were going to win the Second Civil War.

A Royalist force in the north of England would now team with an

army of Engager Scots – the force totaled twenty

thousand men – under the command of Sir Marmaduke Landale

to do battle with the Parliamentary army, with the goal of

putting Charles I back on the throne. Parliament had only half as

many soldiers, but they had Oliver Cromwell, and the enemy no

longer had Prince Rupert.

It was no contest. By October, Cromwell was deep into Scotland,

where he had no difficulty coming to terms with the Marquis of

Argyll, a Scottish Chieftain and Presbyterian who had not

approved of the Presbyterian Engagers joining forces

with the English Royalists. The agreement stated that none of the

Engagers who headed south would ever hold office in

Scotland again. When Thomas Fairfax conducted a successful siege

at Colchester, the Royalist garrison surrendered and the Second

Civil War ended in victory for the Parliamentarian army.

Still, there was a peace party in Parliament who thought

negotiations were possible with Charles Stuart. No doubt they

could not accept life without a monarch as their security

blanket. But by this time, both Oliver Cromwell and Thomas

Fairfax believed that negotiations with the King were impossible

and he must be deposed – though Fairfax would never support

his execution – and led the fight to expel the members of

the peace party from Parliament. On the 27th of January

1649, Charles Stuart was condemned to death as a tyrant and a

traitor by sixty-nine members of a high court that was appointed

to try the King. The days of manipulation and negotiation were

over, and Stuart's stubbornness – he would always insist he

ruled by divine right – had led him to the block. Until the

end he would deny that the common man should have a say in the

affairs of his country. The story that Oliver Cromwell laughed

when the axe fell is not true; he wasn't even in attendance.

|

Charles II and

Covenanter Scots

|

|

But now Cromwell would have to deal with King Charles II, and

this nineteen year old would prove just as unscrupulous as his

father while attempting to regain the throne. This meant that

Oliver Cromwell, now the undisputed top soldier in England, must

once more take to the battlefield if he wanted to keep the

republic he had helped establish. The Third Civil War would last

from 1649 to 1651, and would end with a beaten, Charles II

scurrying back to the protection of Holland, from whence he came.

Charles II knew he could not attack England directly; it was

under the tight control of the new republic. But he could attack

through Ireland and Scotland, where he thought he would have no

trouble recruiting allies to his cause. However, he knew it could

not be a combined effort of Irish and Scottish soldiers, since

the two countries, one mainly Catholic and one mainly

Presbyterian, did not get along with each other, and the

likelihood of their combining forces was small. He chose Ireland

as his first landing point, only to find that Oliver Cromwell,

who had been appointed Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, was already

there with an expeditionary force of twelve thousand men. He had

arrived, said Cromwell, to undertake the great work against

the barbarous and bloodthirsty Irish. Cromwell uttered these

words because the Irish Rebellion of 1641 had supposedly been

responsible for the murder of three to five thousand English

settlers – a story that has never been proven.

The Marquis of Ormonde had been appointed Lord Lieutenant of

Ireland by Charles I in 1644 and had succeeded in fashioning an

army of Old Irish, Anglo Irish, and Catholic Irish, who were

Lords of the Pale. It's doubtful if either of these

groups considered themselves Royalists but had joined the fight

due to self interest.

Ormonde got a taste of what he was up against when his combined

Irish army was easily defeated by three regiments of now English

Commonwealth soldiers under the command of General Jones, that

had been dispatched by Oliver Cromwell upon landing in Ireland.

The battle occurred just outside Dublin and Cromwell tarried

there for just a short time before leaving to besiege Drogheda,

where the remainder of Ormonde's troops were waiting.

The siege of Drogheda is not so much notable because of a

Commonwealth victory as much as it is for the uncharacteristic

behavior of Oliver Cromwell and his men. Heretofore the Roundhead

behavior during and after battles had been exemplary and in

keeping with their Puritan standards. They did not

plunder, they did not rape, they did not murder; which certainly

couldn't be said of their opponents or their Scottish

Presbyterian allies, who after all, considered themselves God's

true servants. But Drogheda, even today, is used to portray

Oliver Cromwell as a monster, and has forever been a stain on his

name and made him the bogeyman for all Roman Catholics. Drogheda

was a walled city with the river Boyne running through it. Behind

the thick walls were twenty-three hundred soldiers, mostly Irish

but not necessarily Catholic, who were commanded by Sir Arthur

Aston, a Roman Catholic.

Cromwell's cannon started firing on 10 September 1649.

Immediately he sent a message to Aston, asking him to surrender,

otherwise he would not be responsible for the consequences. It

must be stated here that no quarter was a standard rule

in seventeenth century warfare for those who refused to

surrender.

Initially, Aston put up a spirited defense, despite the fact that

two breaches in the wall had been made. Cromwell lost many good

men before deciding to lead the next charge himself, wearing a

red scarf and screaming no quarter! The effusion

of blood that followed was no doubt the worst of the Civil Wars.

Every tenth surrendered Irishman was put to the sword; and even

today, The Curse of Cromwell is heard on Irish lips as

the story is told to Irish children.

Cromwell never apologized for Drogheda. Indeed he was heard to

say that he prevented greater blood loss in the future by his

actions that day, and it's certainly true that some Irish

garrisons fled in panic, rather than face Cromwell. One Irish

officer declared that if Cromwell stormed hell, he would take

it. Cromwell never said that Drogheda was revenge for the

massacre of Englishmen in 1641, but if so, revenge was gained.

In October of 1649, the port town of Wexford suffered the same

fate as Drogheda when they refused to surrender. Conversely, the

garrison of Ross, which did surrender, was allowed to march away

with arms, bag and baggage, drums beating, flags flying,

bullet in mouth, bandoliers full of powder and match lighted at

both ends, and the inhabitants were protected from violence.

The town of Kilkenney was the next to surrender and received the

same fair treatment. But the Irish resistance was not over.

The town of Clonmel was brilliantly defended by one Hugh O'Neil,

and cost Cromwell many men; but O'Neil was low on ammunition, and

slipped away during the night. No reprisals were taken on the

citizens, and Cromwell paid credit to his gallant foe.

By May of 1649, the Irish war was over, as many Royalist officers

surrendered with the promise of safe passage. Charles II could

not attack England through Ireland; but their was still Scotland,

and he still wanted the throne he saw as his. The Scots knew they

were the young King's only hope for reclaiming the throne, and

they lay down very stringent terms. In an agreement called the

Treaty of Breda, Charles even acceded to Presbyterianism

being the official religion of England, and agreed to forbid the

practice of Catholicism anywhere in his dominion.

To understand what was happening in England and Scotland in the

seventeenth century, we have to know that even though nowadays

the two countries have been united as one for three hundred

years, this was not the case in the days of Cromwell; as the two

countries were bitter enemies. Scotland had always wanted a Scot

on the English throne, and saw Charles II as just the figurehead

they needed. When Cromwell and the new Commonwealth saw what was

happening, they knew they must now make war on Scotland.

This war would be fought without the participation of Lord

Fairfax. He had refused participation in the new Commonwealth

government because he opposed the execution of Charles I. His

wife was a Royalist and a Presbyterian, and since, in his mind,

there still existed a covenant between Scotland and

England, he would not invade Scotland; and he was washing his

hands of the new Commonwealth government, despite the

begging of Cromwell.

But in a military sense, Fairfax was no longer needed. Cromwell

was now the man, and on the 22nd of July 1650, he led

sixteen thousand men in an invasion of Scotland, and by August,

was trying to surround Edinburgh. He was opposed by a former

ally, David Leslie. Charles II, who was proving to be as devious

as his father, was seemingly willing to do anything the Scots

wanted, including pretending to embrace Presbyterianism while

hating the accompanying religiosity. He even renounced his

parents, while declaring privately that he was still a true

Anglican. Charles wanted the throne, and he would deal with the

crazy Scots once he got it.

In a war whereby enemies could become allies, then enemies again

in a very short time, Cromwell and his Commonwealth soldiers

defeated Leslie's Presbyterians in the Battle of Dunbar –

Presbyterians because, by this time, the Scots had

decided that only the religiously pure were qualified to fight

with them. Though Baptists, Catholics, and others were willing to

defend their country, they were cast aside by these people whom

Charles was depending upon to help him ascend the throne of

England. By the time the Battle of Dunbar was over, three

thousand Scots were dead and five thousand – half their

army – were prisoners. Now, the stage was set for one final

battle in the Third Civil War between the Cavaliers and

Roundheads.

On 1 January 1651, the Covenanter Scots crowned Charles

II King of Scotland. It took a while, until 2 June 1651 to be

exact, but Charles now had the power to see to the repeal of the

Act of Classes, the ridiculous law that had been put in

effect to keep the Scottish army Covenanter pure. Now,

the movement to recapture England from the Commonwealth, and

restore the monarchy, again took on a political or Royalist

flavor, as opposed to a religious one. Every man who could

possibly fight would be needed for the final struggle, which

equated with the defeat of Cromwell. Religion didn't matter to

Charles II, only the restoration of the monarchy mattered. He had

what he thought was a brilliant plan, but he was up against the

master.

For some time a movement to recruit as many Royalists in England

as possible had been ongoing. The news had gone out that Charles

II had been made King of Scotland and intended to come to England

to reclaim the throne that had been taken from his father. It was

hoped that the Royalists who had been kept in submission by the

Commonwealth would be ready to move.

Actually, Charles and the Scots had decided, after the Battle of

Dunbar, that their only hope for victory was to head south to

England, picking up support along the way, and fight the final

battle on English soil. It was either that or face being

surrounded and destroyed in Scotland. By heading south they could

cut Cromwell's supply lines, and force him to head back to

England with a hungry and under supplied army. But thanks to

spies, Oliver Cromwell knew exactly what was happening and was

not worried. He knew there would be no flocking to the Royalist

cause, and he also knew how tired any army would be after

marching three hundred miles in three weeks. Taking the eastern

route to England, and going through towns that would supply food,

Cromwell would arrive in England just four days behind the Scots

and their young monarch, who had not much love for his army, and

they having little love for him.

The moment Charles Stuart and the Scots, along with not many

Royalists picked up along the way, stopped to rest in Worcester,

Cromwell promptly surrounded them. Although the Royalists fought

bravely, Cromwell, the master tactician, completely controlled

the battle that followed. This was complicated by the fact that

the Royalists fought without the leadership of David Leslie, who

had resisted going to England, and took little part in the

battle.

When the battle ended, one of Cromwell's chaplains said: When

your wives and children ask you where you have been, and what

news: say you have been at Worcester, where England's sorrows

began and where they have now ended.

To give credit to Charles II, the young King, after forty five

harrowing days, made his way to Holland, then to the arms of his

mother in France, where he arrived in such a dirty, disheveled

state that some didn't recognize him. He reported that he was

safe because of those who still loved him, the common people. He

also said that during his escape he saw a side of the English

people he never knew existed. Clearly, even some commoners still

wanted a monarch.

Oliver Cromwell had fought his last military battle but it would

almost seem that the battles he was now to fight would make him

yearn for the simplicity of the battlefield. To make matters

worse, he would have other struggles, against the various

diseases that would rack his body. He had contracted Vivax

malaria during one of his campaigns, and even though it was not

the fatal kind, it would torture him for the remainder of his

days. He would also suffer from gout and kidney stones, while

boils would plague him periodically. Cromwell had always had

warts, especially on his face, with a particularly large one on

his chin, which did nothing to enhance his appearance. When he

came back from the wars a hero of England, he sat for a portrait.

The artist asked him if he wanted the painting without the warts

showing. Cromwell replied: Sir paint me as I am, warts and

all. It's a saying that has lasted to this day.

|

Oliver Cromwell

– warts and all

|

|

What Cromwell wanted now was peace. He also wanted forgiveness

for the enemy, even though it would be awhile before they could

be welcomed into the government. He suggested that the Rump

Parliament that had been elected for the wars be dissolved and a

new one elected; but he lost his first fight as a statesman when

his proposal was voted down. He would make impassioned speeches,

many times shedding tears, to try to inject his ideas into the

process, seemingly knowing that he now had the power to launch

himself into the highest office in the Commonwealth, which he

did, but he refused to be called king.

His title was Lord Protector, though he made many

enemies of those who wanted a monarch. It was obvious that some

were homesick for the old ways, but if they wanted a dictator,

Oliver Cromwell was not their man. True, he still had great

friends in the army and used them on more than one occasion to

stop a process he knew would be bad for England. The England of

the seventeenth century could never be a democracy, as we have in

the United States today, but at the time, it was as close as

Europe, and probably the rest of the world had ever come to one.

To Cromwell's mind, the wars had been fought for religious

freedom, and he did his best to make it happen. There had been no

Jews in England since 1290, but Cromwell invited them back, and

they came. He envisioned a state Church that tolerated all

religions, though he could never bring himself to be totally

tolerant of Catholics, probably because he was adamant that

anyone could have direct access to God. He did have many

conversations with Catholics, which had been unheard of in

Anglican England.

Money was raised from fines levied on those who fought for or

supported the Loyalists; although they protested, this has

occurred throughout history. For defense, a horse militia was

created and was a cause for disagreement among Cromwell and his

first Parliament as to who should control it.

To keep the peace and prevent plotting against the government,

the country was divided into eleven sections and controlled by

eleven major generals, most of whom were Cromwell's close

friends. These major generals caused some grief to Cromwell

because of their heavy handed methods of promoting morality.

Cromwell soon came to realize that you can't make people be good.

A constitution of sorts called The Instrument, was

written and approved. Many times, out of frustration, Cromwell

had been tempted to rule by the sword, but didn't because he

realized if that were done, The Instrument would become

invalid. Cromwell was ahead of his time in believing in

freedom of conscience. Only once, in 1655, was he

compelled to put order first, and institute what we would call

martial law. He hated this dilemma of statesmanship.

Under Cromwell came three main Constitutional results that were

never reversed; the feudal rights of the Crown, and the Tudor

Prerogative were never restored. No longer could the Protector or

King levy taxes without the consent of the House of Commons. Nor

could the King arrest legislators without showing cause, as was

done before. And since Parliament won the Civil Wars, it became a

permanent part of the Constitution. The Church of England had to

recognize that dissenters had rights, and they became permanent

and influential members of society. And finally, the most

important change of all: capital punishment was meted out only

for murder and treason.

Indeed, one of the few things that Cromwell did wrong was to

become sick and old too soon. Had he lived ten years beyond his

death date of 3 September 1658, the Constitutional form of

government may have become so ingrained that going back to a

monarchy would have seemed repugnant. As it happened, his son

Richard was not strong enough to provide the leadership required.

Anarchy ensued and Charles II would gain the throne after all in

1660.

After Cromwell's death, his enemies could not let him rest. On 30

January 1661, the coffin containing Oliver Cromwell was taken

from Westminster, put on a sled and taken to Tyburn, where his

bones were taken out of the coffin and hanged. The corpse was

then decapitated and the head mounted on a pole atop Westminster

Hall. Wherever Cromwell was, he no doubt smiled and forgave his

enemies. The Royal Family of England has apparently never

forgiven Oliver Cromwell for what they saw as a theft of their

throne. In 1911, Winston Churchill wanted to name a ship –

the Cromwell – but George V said no. As late as

1950, a motion to name a college after Cromwell was defeated.

Bibliography:

Charles II, His Life and Times by Fraser

The Greatness of Oliver Cromwell by Ashley

The Battle of Naseby by Ashley

The English Civil War by Ashley

Cromwell, The Lord Protector by Fraser

by Don Haines

... who is a U.S. Army Cold War veteran, American Legion Post 191

chaplain, a retired Registered Nurse, and freelance writer; whose

work has previously appeared in this magazine as well as in

World War Two History, and many other

publications.

|