The Fight

"And he was driven from men, and did eat grass as oxen, and his

body was wet with the dew of heaven, till his hairs were grown

like eagle feathers, and his nails like bird claws."

the reduction to madness of King Nebuchadnezzar of

Babylonia, conqueror of Jerusalem, in The Book of Daniel

The stained grill cloth of the citron Crosley radio

pulsated with Dinah Shore's I Wish I Didn't Love You So,

and, for the third time in fifteen minutes, the back of the boy's

skull slammed into the forty-gallon water tank. He staggered

against the side-arm kerosene heater, wrapped one gloved arm

around the conical steel draft diverter, wobbled, and finally

tail-ended onto the chill, damp cellar floor. The acrid smell of

lime mortar, fused with mildew, seared its way up his nose. A

metallic taste welled up in his mouth as though he'd just been

sucking soda through a copper tube. The ceiling rafters swirled

round like the wares of a Jap chopstick factory that had just

taken a direct hit from one of Doolittle's B-25s.

With his other glove he shoved away a mass of thick dirty blonde

hair clotted to his sweaty forehead and rubbed his square

Dick Tracy jaw. The sloshing sound in his ears –

was it just the water in the tank or what was left of his brains

swashing round in his head? "Jesus, what you fixing to do? Turn

me into a drooling idiot?"

With his ungloved hand, his father took a long drag on his

Camel. "You're there already, Sad Sack. Three

times I told you to keep your left shoulder and foot forward and

your left fist ten inches in front of your chin. But you, you

rather pretend you're a windmill. A left hook isn't a wide swing.

It's mostly a twist of the body, Joe Palooka. And you

telegraphed your right cross by drawing your fist back from your

guard position. You ain't never gonna send that bully Sean

Cummins to Slumberland like that. And just so you don't

think I'm getting soft, there's only one reason I'm not undoing

my belt to tend to your cussing little ass. I'm assuming, after

that punch, you figured you'd died and gone to Heaven and mistook

me for your Lord and Savior."

The kid chuckled. "The day I start taking you for Jesus ... well,

I'll be ready to play Tiddlywinks with the squirrels.

I'll check myself into the Bughouse. I ain't that punch-drunk

yet."

His father laughed. "Yeah, me as Jesus, that is some stretch,

ain't it?"

"You ain't whistling Dixie," the boy replied. He folded his

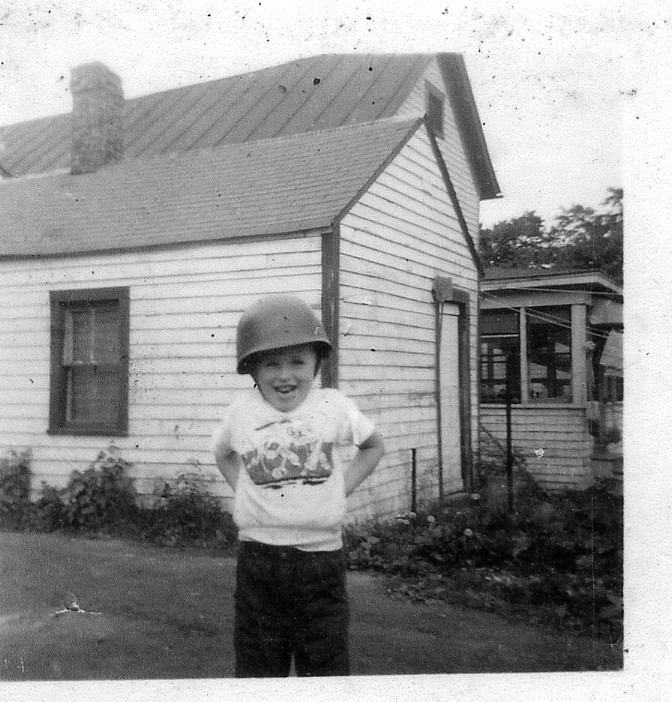

gloves prayer-like over a small but well-defined chest covered by

a tattered white Davy Crockett t-shirt. "Gentle Jesus, meek and

mild, please don't dust this little child."

His father flipped the butt into a rusty floor drain, where it

hissed, sputtered and died. He brushed a shock of raven-black

hair out of his eyes and rolled down the sleeve of his spotless

white dress shirt. Then he leaned down and jerked the boy up by

his collar and yanked his face up close to his, scowled, then

grinned. "If you were as quick with your fists as you are with

words, old Sean'd be sleeping in the boneyard now. As it is, I

wouldn't take hundred-to-one odds you'll live to be twelve.

"Aw, it ain't fair. That Sean's fourteen, and he's got thirty

pounds on me.

"Fair, huh, kid? Get me a crying towel, and I'll wipe your snotty

little muzzle. His father unlaced his glove, hurled it into a

khaki duffel bag and broke out a chromed Zippo lighter

decked out with a leering skullhead – his lucky piece that

he had carried as a jungle scout all the way through the War in

the Pacific.

He lit another Camel, dangled it from the corner of his

mouth, and unlaced the boy's gloves. "After Pearl, the first

thing we learned in jungle training was to knock that word out of

our vocabulary. Our sergeant was a bantam of an Irishman who had

been with O'Ryan's Traveling Circus in WWI, the 27th

Division. He was showing us the fine and manly art of hitting a

guy below the belt. A real character he was, all five feet three

of him, with a twitch in his left eye and a z-shaped white scar

on his forehead – a little beauty mark he picked up in

France. I raised my hand, with a goofy Howdy Doody grin

on my face, and said, 'That don't seem on the up and up, Sarge.'

"And Sergeant Z double-timed right over to me, with his eye

twitching like mad. 'Up and up, Private Numbnuts? I wouldn't give

a plug nickel for your ass out in those jungles. You're gonna be

down and down out there, Sad Sack. Who the hell do you

think's running around in those bushes? Little Lord Fauntleroy?

Yeah, that's who's mincing around out there. And instead of a

Sears, Roebuck catalogue to swipe his ass, should the need arise,

he's toting a copy of the Marquis of Queensbury rulebook to read

and abide by.

"'Oh yeah, and little Miss Shirley Temple's out there too,

throwing a tea party. You just listen real careful one night and

you'll hear her singing On the Good Ship Lollipop.'

"Then he hopped back like a rooster and addressed the others.

'This here shit-bird, men, is Private Flatpeter, alias, Private

Pumfrits, Fried Potatoes, late of the S.O.L. Division. He's

already pushing up the daisies. He's gonna be out of the trenches

by Christmas, put in a bag. Repeat after me, for his sake, all

together, or as we used to say in France, toot and scramble,

Yea, though I walk through the Valley of the shadow of

death ...." And they all muttered the Psalm right after him.

He turned away as if Last Rites for the corpse were over, but

then he spun round and kneed me in the groin so good I doubled

over. I thought I was gonna decorate my boots with the sinkers I

had for breakfast. He whirled around to the others and said,

'Now, boys, was that fair?' 'Yes sir!' they all yelled. 'Any

questions, idiots?' And all the guys yelled out, toot and

scramble, 'No sir!' "Three beans, clowns," he yelled back, "three

beans." My buddy Mac, who taught French before the War, told me

that was Z's twisted version of Froggie-phone for Tres

bien, or Very good; just like toot and scramble was his way

of saying, tout ensemble, or all together.

"Then he yanked out of his pocket some piano wire. 'You know why

I carry this, Private Flatpeter.' By then I was mad and I

smart-mouthed him. 'I dunno, Sarge. Maybe in case you run into

Cole

Porter tickling the ivories for Shirley and he's broken a wire on

his piano.' He booted me in the left kidney.

"'Oh sweet tit of the Virgin, sweet milk of our Savior, you're

gonna pay me drills. This, Pumfrits, is to cut off some sentry's

airflow – a fool who didn't keep his mind on business, like

you.'

"Some of you got the wrong notion. You think you're a bunch of

Gary Coopers playing Sergeant York. You think you're gonna go out

in those jungles, make some turkey sounds, and 132 scared Nips

are just gonna stick their hands up and say, 'So solly. We

sullender. Prease to forgive for Pearl.' Oh they'll stick their

hands up all right, but it'll be up your cherry asses. You think

you're gonna be John Waynes – guys in white hats.

No sireeee, assholes, you're gonna be the guys in black hats. I'm

gonna teach you to think like gangsters, hitmen. By the time I'm

done with you, you could work for Al Capone after the War if he's

ever makes a comeback. He grabbed this giggler out of the line

who looked like Caspar Milquetoast. "See this loggin. He's gonna

be the Enforcer, the new Frank Nitti."

"You're all gonna be the nastiest snakes in the jungle, condemned

to crawl on your bellies through the grass just like the devil

serpent after he went and screwed up Adam and Eve's cozy little

Garden setup. Yeah, that's me. I'm the head serpent, the Devil

himself. Get down and give me one hundred pushups, all of you,

toot and scramble. Worship your new god.' Then he danced around

us while we huffed and puffed, yelling when he was finished with

us, if we did find Shirley out there, hey, if we found our own

sisters out there, we'd ... well forget that. We thought he was

nuts, but he sure as hell put the snake in us after eight weeks.

"But Private Flatpeter still had to learn the hard way. On

Guadalcanal, I was out late one afternoon scouting and came

across a half-dead Jap. Bad shrapnel wound, like his leg had been

put through a meatgrinder. Muscle, bone, leggings – they

were all swapped around. So I haul him up and start cutting his

leggings away with my Kabar. Well he's a- moaning and

groaning. And then he slaps his leg real hard. I figure it was

because he was hurting so bad.

But that wasn't his game. He had a grenade hidden near his

doohickey and he had pulled the pin and plunged in the fuse all

the while Doctor Kildare was practicing medicine without

a license. But then he made a mistake. Pulled the grenade out of

his bloomers. Don't know why. He was ready to sacrifice me and

himself for Hirohito, but maybe he got squeamish about his

privates and decided to create some distance between them and the

grenade. Maybe he didn't want to spend all eternity on the rag. I

caught the grenade out of the corner of my eye and turned round.

He was grinning a big buck-toothed grin, just like one of those

Nips in the movies. Problem for him was he was holding a Type 91

which had a seven-second delay."

"Seven seconds?" The boy whistled. "A guy could take a pi–"

"Right kid, right, if he were so minded." His father gave him

that puzzled look as though he were still trying to figure where

his good little Catholic boy learned to talk like that. "But a

type 91 wasn't just for hand tossing. Could be used as a

projected munition, in a 55mm knee mortar. If you got a grenade

in a pipe between your legs you want something that's not gonna

go off lickety-split. I knocked it out of his hand with my

Kabar, came back and cut his throat right here." He

pointed to a spot on his neck,

"Geez, the carrot artery," the boy said, with his hand around his

throat.

"Carotid, Numbnuts, carotid. Then I flipped him on his side and

ducked behind him, but my left arm caught shrapnel. No pain, more

like a baseball bat had slammed into me. That's those dotted

scars on my left forearm. Still some steel deep in there."

"Don't I know it!" the kid said rubbing his square jaw, the image

of his father's.

His father thrust the gloves into the bag, knelt before the boy

and gripped both his arms just above the elbows. "Don't ever talk

fair to me, kid. Life ain't on the up-and-up. Your

brother choking to death with the polio in that iron lung –

you think that was fair? Jesus, I wanted to shoot holes in it

with my .38, rip that damn metal tube apart with my bare hands,

force my hands against Pete's shoulder blades till he started

sucking air again. And afterwards, your mother hitting the bottle

and taking a powder to California ... And that War – what

we had to do out there – what we had to become to do it. We

crawled all right, tooting and scrambling, tooting and

scrambling. When I'm on special detail down on the docks and some

punk comes squirting lead at me with his .45, you think I just

stand there and say, 'Hey no fair, buster. Time out, time out. I

only got me a lousy .38. Gimme time to go home and get my .45.'

"You get a guy down who's out to hurt you, you gotta hurt him,

hurt him so bad the next time he sees you he starts shaking and

puking. This river neighborhood ain't changed since I was a kid,

back in the Depression. Always bigger fish looking for smaller.

You get the chance, you give him the works – in spades.

Guys like Sean you gotta fix or they'll never lay off. They'll

always be back. Knee him if you get the chance, slug him when he

doubles up, and when he's down, kick him hard in the kidneys,

here just below the ribcage." A finger of his left hand jabbed

the boy's back, and the kid squirmed as he felt a knot of pain

corkscrewing up through his diaphragm. His father gripped his arm

again. "If he rolls over, give him another kick in the balls.

Keep hurting him so he'll never wanna come near you again. You

gotta be hard, boy, or you ain't never gonna get on with Sean or

anybody else in this damn life."

Their eyes locked together. When he was eight and his father

talked about the War, he peered into those eyes and saw only

cerulean blues, like the pictures in magazines of the Pacific.

But as he grew older, he began to see shades of green there

– dull yellow green, bluish green. And that too was like

the Pacific. Lately – since Pete and his Ma – he

began to see other greens – some like the bottle green on

the bellies of flies that flickered around the pails out in the

shed where there was always the smell of rot, and some so deep

they were black like an avocado that had lain around too long.

And that too was the Pacific. He remembered his father telling

how he sailed up through the Gap toward the Philippines, after

the campaign at Guadalcanal and how a sailor told him he sure as

hell hoped they'd weren't torpedoed there, because it was a

five-mile one-way trip to the bottom.

That was the darkness he saw in his father's eyes now. He saw

himself as a GI on that ship spiraling downwards into a

bottomless darkness and below him, pulling on his heels, was his

father with a mug that looked like a grinning devil god. The

feeling in the back of the boy's hands was disappearing, and he

felt he could no longer flex his fingers. His lungs were

blackened by the updraft from the Camel.

"Dad, Numbnuts' arms are turning numb too."

His father flushed and released his grip. "Time for you to get on

your paper route. And stay away from Sean. You ain't ready yet.

I'm counting on you for the party tonight, unless you got

something better to do."

The boy laughed. "Sure, Dad, I got me a heavy date, playing

kissy-face with a coal truck."

On the planked porch, scabrous Hunter green paint cut into the

boy's knees as he knelt and crouched, rolling and shaping his

papers into the form of small baseball bats. He shoved them into

a canvas bag smudged with newsprint as black as his T-shirt. He

breathed in the smell of damp newsprint and rubbed his blackened

hands against his spotted shirt. The ink smelled almost as good

as gasoline, fresh out of the pump, at Joe Blake's Shell

station.

A guy'd have to be a blink to confuse him with Mr.

Clean, but tough titties. He'd have to take a bath tonight

and stick his head under the faucet before the party – even

put on a white shirt and tie so he'd look like the other mugs at

the party. So, if anybody didn't like them apples – like

Mister McCreary, who nicknamed him Ragged Dick –

they knew what they could do, and he'd be happy to give them one

of these papers, nice and tightly rolled, to do it with.

In the headlines, Ike was recovering from his heart attack. Back

in September, Sister Marie had made them all get down on their

knees on the hard oak floors and pray three whole rosaries. After

twenty minutes, his kneecaps felt like someone took a

sledgehammer to them. On his seventieth Hail Mary, he

turned into Jimmie Doolittle and began to spin round the crucifix

part of his rosary, now the propeller of his B25 headed for

Tokyo.

Sister Marie came up behind him and clunked him in the head with

her wooden clapper. "You better pray, you little bastard. Aw,

Jesus Christ, yes. Because if the President goes tits up, the

Commies'll be over here quicksville and the first thing they'd do

is round up all us Catholics and machine gun our sorry little

gutter hype asses." Those weren't her exact words, but the way

she rolled her head and swung her rosary around as she yammered

on, they were largely to that effect.

God, he had a funny old man. He was proud of him, proud of the

way he served, and all the medals he brought home. Real tough

guy, but sometimes he could be gentle too – come into your

room at night and pull the cover over you, just like his Ma used

to – until Pete died of the polio. Then she started hitting

Nick's tavern and the bottle and finally him too when his old man

wasn't around – and then one fine June day when he was at

school studying his Baltimore catechism – thou shalt kiss

thy father's and mother's tail and all that hooey – she

took a powder for California. How come God didn't set up an

eleventh commandment: Remember thou to stay off the amber

fluid and dump thou not thy kids?

Yeah, his old man was A-1. Some times, though, Mike could explode

at the littlest things. But at least he wasn't a mean drunk like

Sean's dad who had been at Pearl on the Arizona and now

smashed Sean around whenever he got stinko, as though his

buck-toothed kid had been a Nip piloting a Zero that Sunday

morning in

December '41.

Or like his Ma. That time he and his best pal Frankie from the

trailer park had plopped themselves on a rock outside Nick's

Tavern and kidded all the drunks that stumbled out: "Hey

Jiggs, better get home. Maggie's been up and

down the street with a rolling pin looking for you." Most of the

lush hounds just laughed and stumbled away. Some flipped a bird,

and others called them names the boys had never heard, which set

them laughing – names like bindle-stiffs,

door-matters, flukers, gump-glomers.

Every one of these the boy, a born wordsmith, treasured and

stored up for future reference.

But toward dusk, a floosie in a black dress, with a cloche that

dropped a veil net over her face, had stumbled out bongoed,

assisted by Nick who gripped her elbow. "That's it for tonight,

Gertie. This is a decent gin-joint, not a two-bit nautch-joint.

You're gonna get the cops on me." And the boy had stood on the

rock and yelled, "Hey Blondie, better get home.

Dagwood's roast beef is burning." Frankie had grabbed

him by the arm. "Nix, nix, ain't that your Ma?" For a moment he

thought he pissed his pants, but it was just all the blood in his

body draining down into his feet. She came up to the rock.

"Making fun of your own Ma, huh? You get your ass home and wait

for me in the kitchen. I'm gonna make something burn."

His father was away, so it was no-holds-barred-time. When she

finished giving him the business, he didn't stir out of bed for

two days, and even then he was still limping. Told his old man he

fell off his bike. Frankie said when he saw her heading after

him, he knew the score and wanted to pick up a tree limb and

smash her in the squash. "Sure, sure, Frankie, then we could have

drugged her body into the bushes, hopped a freight down on Water

Street, and went on the lam to Chicago to join up with the

remnants of Capone's outfit."

No, his old man could hold his liquor. He was real lucky that way

and if his father did knock him around, did take the belt to him

now and then, it was his own fault or it was to toughen him so he

could take care of himself. So everything in his life wasn't

jake, but that was just too bad. What was the old Army

expression for just doing your best? He'd just have to battle the

watch.

But Mike could really explode too. The boy struck a rolled

newspaper against his palm. That afternoon his father came home

and his puppy Spankie had pissed all over his father's chair ....

First his old man's face reddened, then went all white, but he

didn't yell. He spoke in a low controlled tone, like one of those

guys in a B-crime movie who catches up with a squealer, smiles,

and tells him how he's gonna get it, usually in the belly, so

Mister Squealer'll have plenty of time to think about it, and how

it's gonna hurt like the dickens. "Listen up, kid. You get that

mutt to stop pissing in my house or I'll dry him out –

permanently. I mean it. He and I'll take a little stroll out the

kitchen door, and only one of us'll have a round-trip ticket. And

in case you don't get my drift, the returnee'll be walking on two

legs, not four." He tapped the butt of his .38 police special

lodged in a black Mexican-tooled shoulder holster under his left

arm.

"Aw, you wouldn't do that, Dad."

His father leaned down. "You have any idea how many guys I sent

down the long road in the War? You think I'm gonna lose any sleep

over one mangy mutt? You think –"

But the boy was already rolling a Batman comic into a tight

cylinder and heading for the kitchen where he found the mutt with

his head in his water bowl and pissing out the other end. "Jesus,

Spankie, if you ain't living the Life of Riley." He

started whacking him real hard, three or four times and yelling,

"No!" "You want to go for a walk out back with my old man?" He

kept smacking him until his father came behind him and grabbed

his arm. "Just get his attention, kid. You ain't gotta knock the

bejesus out of him."

No, he didn't have to do that. Three days later, a coal truck

backed into their driveway and played out that little scenario.

Knocked the bejesus, the beshit, the bepiss, the beguts smack dab

out of him. All that was left, after the crows chowed down, was a

stain in the driveway's ashes. He stood over it and cried. "Oh

Mother of God, I'm sorry, Spankie. Jesus, I'm sorry for that time

in the kitchen." In his mind, he swore the stain had muttered

back at him, "Too late. Up your brown, buddy."

Yeah, his father was a killer all right. The first time he

examined his War scrap book he found photos of Jap soldiers. "Who

are these guys, Dad?" "Some guys whose Christmases I cancelled."

Then he found the pictures of the kids, one a baby all naked on a

blanket stitched with Jap designs. His doohickey looked

different, as though it had a helmet over it. Maybe that was the

way Jap doohickeys looked, funny like their eyes, but he didn't

exactly have a picture gallery in his head to draw on for

comparison purposes. The nuns had him convinced even thinking

about down there was a sin and the only one he had ever seen was

his own, not even Pete's.

"You didn't take them off the payroll too, did you?" "Nope, they

weren't there." The way he said it, the boy thought it was just

jim-dandy for them that they weren't, because if they had been,

his old man would have arranged a family package to Sliceville.

Then he had found a tooth with gold in it, and his father had

clammed up and told to take a hike and start bothering him.

That night at nine o'clock, a breeze came up from the river, and

leaves of the great elms along the walks rustled in air empty for

rain. Squirrels, in an endless search for food, scurried up and

down their trunks, and, to the north, ships with twinkling lights

glided down the St. Lawrence. The boy, in the brilliantly lit

lemon yellow kitchen, pressed his nose against the window's mesh.

The corroded zinc grated against his upturned schnozz, and the

neighborhood's familiar musty smell filtered in. Countless

shadflies up from the river whirled round the single flickering

yellow porch light. He inhaled deeply the fragrance of the lilac

bushes that camouflaged the rotted trelliswork under the porch.

He half turned, stretched, and twisted the treaded brown knob on

the Depression-style cathedral radio. The Philco's hum betrayed a

bad capacitor, but eventually gave way to Glenn Miller's I

Know Why. As the radio tubes warmed, the old wooden cabinet

emitted the smell of shellac that had dried back when Hoover was

promising a chicken in every pot. He remembered his grandmother's

old joke. "Damn fool. We didn't even have the pot to piss in."

Behind him, a cloud of smoke enshrouded his father and his vet

buddies, immersed in their beer and poker game. Bakelite chips

clattered against the Formica table, and that clatter was

punctuated by murmured folds, raises, straight flushes, and

accusations that his old man was trying to steal the blinds. He

grinned, imagining Mike as a second-story man running down the

street with a set of Venetian blinds rattling away on his back.

A thrill shot through his body. It was an A-1 time – one of

those times you'd think back about even when you were really old

– so old maybe you'd be lying in bed with a tube up your

ass, like his great- grandmother just before she croaked. Since

his mother, brother and dog vanished, he had come to think of

life as loss. The trick was to gather up the special times, so

when the bad happened you had the good to think about –

just like a blackbird stores shiny things in his nest. The

special days he called murderistic, after the Jimmy

Dorsey song, which in jive talk meant just jake or

mighty fine. It was his own special word, which he kept to

himself– personal-like.

His great-grandmother had told him life was like a great big

ice-cream cone, triple-scoop. "There's one catch, though, boy.

It's

like you got it served up to you on a hot day in July – a

real scorcher. So you gotta lick it hard, afore it up and melts

away." Sometimes when he thought about his brother Pete, his Ma,

and Spankie, he wanted to pay a call on His Grand Highness,

Mister Good Humor in the Sky, and say, "Hey, buster, do

I look like some rube appleknocker? You rooked me. I only got one

scoop." He glanced round, imagined seventy years from this night,

and they were all gone, and there he was alone with a tube up his

... And the radio wasn't playing Glenn Miller and Dinah Shore but

weird electronic music like what you heard when a flying saucer

showed up in those science fiction films at the Strand. And the

kitchen wasn't a bright yellow, but all cold stainless steel.

But that was the wrong way to think. A guy could get himself real

down thinking that way, turn into a real mope. Tonight was here

and now, and he could enjoy it. So tonight was

murderistic. Out of a shoulder holster his old man had

cut down for him, he flicked out his chromed Hubley

.38-style cap gun and broke it open. A red roll of caps sat there

like an angry rummy's eye. He threaded it up through the hammer.

Around the table there were four cops, Joe, Ernie, and his uncle

Pete and his father, all just off some detail, with their white

shirts and ties, shoulder holsters and guns, just like his

– all police specials – and he was dressed just like

them. Now and then he heard a metallic click as his old man drew

out his .38 and flicked open the cylinder – a routine he

practiced for as long as the boy could remember.

His uncle Pete, grinning like Howdy Doody, was the

youngest, still in his twenties. With his slouch-brim tilted back

over a sprawl of thick raven-black hair, he leaned his gangly

frame forward in his chair. Together, he and Mike, who shared

with his kid a brickwall build and Dick Tracy chin, looked like

that comic book ad in which the muscle job is always kicking sand

in the face of the ninety-pound weakling. But Pete's eyes, like

the others', had what the boy called The Look. That look

– and maybe the Howdy grin too – had been

the last sights a lot of Nip Clarabells had had a gander at just

before they slammed into the ground.

He had seen a similar look in just a few civilians – the

handcuffed guy his father had hauled into the station last

Saturday. Claimed he mistook his wife's head for some petunia

bushes that needed trimming and used the hedge clippers on her.

"Honest mistake," his father said to the booking sergeant, "but I

sure as hell ain't hiring Lawnboy for any yard work around my

place." The sergeant split a gut.

Suddenly Pete snapped one of his suspenders and called out, "Hey

piss-ass, what's a guy gotta do for a drink in this dump, fall

over and clutch his throat?"

"Sorry, uncle Pete."

"Yeah, well next time you will be. I'll lay one upside your

head."

"Yeah? You and what army?" The boy took up a boxing stance.

"Oh Jesus, Mikey's School of the Manly Art of Pugilism

is open again for business." He looked at his brother. "Trouble?"

"Sean Cummins."

"Time somebody settled his hash. Of course, the way old Lester

whacks him around, no wonder the little devil wanders the

neighborhood seeking the ruin of souls." His uncle yanked the kid

over by his tie. "Is that one of those phony clip-on baby ties or

did you knot that four-in-hand yourself?"

"Hey, easy on the threads. I tied it myself. Dad showed me."

"Ok, so I'm impressed, Bright Boy. Here's a pack of candy

cigarettes. And now, kid, I'm dying here."

"Sure, sure, uncle Pete. Thanks."

He snatched his uncle's glass, ducked a playful slap, and turned

the cold brass knob on the thick paneled door with chipped green

paint. It stuttered open. He dashed out into the shed to the keg

stenciled with the label Nick's Tavern. From a half-open

pail of garbage a gust of something rotten struck him. The buzz

of bottle flies transformed into his grandmother's old Depression

favorite, Easy Come, Easy Go. Suddenly he was in New York,

in the Rainbow Room, high above the skyline. He was a waiter

there in a fancy monkey suit in the ritzy restaurant in an old

William Powell-Myrna Loy Thin Man movie. "Spam, definitely

spam with a hint of tuna melt casserole, vintage 1936. And

tonight, Monsieur and Mademoiselle, no

surcharge for the maggots."

He turned the glass in his hand. His old man had picked them up

in Lake George at a honky-tonk souvenir shop. The dilapidated

shop fronted a ramshackle motor court where they had gone on

retreat after his brother Pete sunned his moccasins. Real quality

place – no extra pillows, sheets that smelled like a mummy

had suffered the second death in them. And in the back, a

picture-window view of a cinder dump with garbage cans that kept

the blackbears so happy most of the night they didn't know

whether to shit or go blind. His mother, a Lucky Strike

dangling from her kisser, had yanked back the faded tropical

curtains and cracked, "Geez, the miracle of Cinderama,

and no extra charge." And Mike said, "For five bucks a night,

what'd you expect, the blue Danube?" Yeah, and in the morning you

got up itching yourself to beat the band.

Painted on the glasses in garish pinkish tones was a naked woman

like those dames guys dabbed on planes and bombs during the War.

His mother hated the glasses, but after Mike poured her a few

shots in one, she mellowed. "They ain't so bad, and I reckon

they're the closest I'll ever get to Irish crystal on your

salary."

From Lady Godiva's babaloos, red tassels hung down, like

what you saw on curtains in fancy old houses in movies like

Gone With the Wind. He couldn't figure what they were for,

but there was a poem of sorts inscribed over her head. "When the

beer you swirl, the tassels will twirl." He had shaken the beer

around, but nothing happened. A call from his uncle broke off his

musings. "Hey, Shit-for-brains, in exactly five seconds I'm

coming out there and emptying my .38 into that dawdling ass of

yours."

As the evening drew on, the suds and some jungle-juice from under

the sink loosened their conversation. Master Tin Ear smoked his

pack of candy cigarettes, swigged his Coke, and

pretended to read his Batman comic, all the while his

ears were jacked up like he was an official member of the Mickey

Mouse Club. Ernie started humming Remember Pearl Harbor.

And Joe said, "Yeah and remember Hotel Street in Honolulu. Three

dollars, three minutes." Pete interjected, "Yeah, and Ernie here

got 2.75 back in change." And they all snickered. And Ernie said,

"Yeah, because after you clowns, she was pleased as punch to meet

a guy who knew which end was up." Then someone said, "The kid.

The kid. Can it." And Joe said, "Canned it all right!" And they

all giggled, but the kid didn't get it. After a while they

started up again, and just when it was getting interesting,

someone said, "The kid. The kid."

His father threw a look of disgust his way. "Kid? That ain't no

kid. That's a midget, Dick Tracy Junior. Been hanging around the

station ever since he could walk. He'd pretend to be sucking his

bottle all the while he was picking up everything you said like a

magpie."

Pete added, "Remember that Christmas down at Hess's Department

Store? What was he – six? Anyway, we take the kid to see

Santa. Mike puts him on the old geezer's lap and Santa says, 'Hey

kid, what say we hitch up the reindeer and take a sleigh ride?'

Next thing you know Bright Boy is pulling a Judas on the old guy.

'Dad, Dad, Santa is trying to get me to snort nose-candy, the

white powder, coke!' They all howled at that one, and Joe

spattered his beer on Ernie.

About eleven, they had reached what he called The Stage.

They'd be talking about the War, which he was always wanting to

hear about, but the booze'd work its magic and sometimes one of

them started bawling or yelling which embarrassed the hell out of

him. Guys weren't supposed to do that. Ernie was yammering on

about somebody named Jim and before you knew it, the guy's voice

cracked and the bawling and hoo-hoo-hooing started up.

Ernie leaned toward Mike. "But you paid those Nips back in

spades, Mike. Fixed their assholes or, more exactly, their

pieholes. Yeah, after they got their butchering mitts on Jim, you

hung out your shingle: Mike's Pacific Dentistry. Pain

guaranteed."

Joe and Ernie laughed, but not Pete and his father. Pete pushed

down his hat, and his father's face flushed. Then Mike muttered,

"Cut that shit, Ernie."

"Yeah, good old Mike, the dentist: Catering especially to the

Oriental trade. Walk-ins – welcome. Walk-outs –

forget it.

His father hurled the cards down. "Jesus Fucking Christ." The

cards splattered on the Formica with a sound the boy knew well,

the sharp crack of a hand slapping a face. He studied the

Formica. No embarassing marks there. A marvel of modern industry,

easy to clean, not like a kid's dirty face that lets you trace

perfectly the red imprint of the hand that smacked it. He could

draw his mother's hand in his sleep.

There was a nearly profound silence – just the hum of the

fluorescent fixture, the crickets in the backyard, and on the

river a fog horn moaning low. The radio sputtered static, as

though Glen Miller had latched on to Dinah Shore's tassels and

headed for the powder room.

The kid's jaw first slackened. Then his fists clenched till his

nails cut into his palms, and he clamped his lower lip between

his teeth – exactly what he did, when his Ma was working

him over with a belt, so he wouldn't bawl. He nearly sucked down

his candy cigarette. Sister Marie had told them there were

certain four-letter words, if Catholics uttered, their tongues

would turn black forever, way past the Last Judgement, and, by

intuition, he knew this was one of them. And combined with the

Holy Name, Mister J.F.C. Himself – you'd have to roll your

tongue around in the coal bin for two years to get it that black.

For a moment, he imagined the official three censors stamping

their bimbo glasses on the table and chanting, "The kid. The kid.

The fucking kid."

His father shoved his chair back, scraping the pitted chromed

legs into the cracked fifty-cents-a-yard linoleum. The back door

slammed in his wake. Pete stood up. "Jesus, Ernie, don't you know

when to cut the yap and dummy up?"

"Oh, Jesus, Mary and Joseph, I'm sorry, Pete. It was the booze,

the damn booze." An old saying from the War came into the boy's

mind. Loose Lips Sink Ships. Somebody's rubber dinghy

had taken a direct hit.

"Yeah, I know, Ernie. I know. You guys take a walk down to Nick's

and take a piss. I'll get him back." Joe and Ernie staggered past

the boy – so slathered they were strutting along side by

side like Frankenstein and the Wolfman doing

the Foxtrot's conversation step. Pete went out the back door.

From the rear screen window, the boy saw their two forms hunched

together on the back steps, just like him and Frankie when they

trying to figure whose cellar window to toss a rock through some

particular night. The boy drew a metal stool up against the

window and pressed his ear against the screen as though he were

listening to The Shadow on the big Philco in the

living room or playing Father Malloy in the confessional

preparing to hear a recital of sins.

"Christ, Mike, after Jim, we all went crackers. Ain't no denying

it. We were like animals crawling through the grass. But that's

over, Mike. We ain't done nothing like that again."

His father turned to his brother. "We were all hungry out there.

Some mornings I woke up with such a pain in my gut I figured a

Nip had slipped into my hole in the night and gutted me. But the

way they hung him up, cut him up like they were slicing steaks

off a side of beef. Jesus, Jesus. I wanted to get a flamethrower,

burn that whole island down. If the A-bomb had been around, I

would have strapped myself to it and rode it down to ground zero.

Destroyed every bit of evidence that any of us – Nips or

Yanks, it didn't matter – had ever been out there.

"But that boy whose teeth I knocked out ... I swear I didn't know

he was alive. Sometimes I wake up and I feel like I'm holding the

Kabar in his mouth and he starts screaming and choking

and all that sticky blood and drool is flowing over my hands.

What happened to us out there? We were Americans, a bunch of

Andy Hardy types. Sure, we came from nothing, but we

were still clean-cut Catholic kids with a sense of right. Jesus,

we were Americans. Americans!" He placed his finger against the

side of his head. "That tapping sound the Kabar made

– sometimes a guy next door can be hammering a nail or the

pulldown on the shade'll tap against the window sill, and it's

all back in here again."

"Look Mike, the training, the jungle got into us all after a

while. It was as though there were someone or something lurking

in that kunai grass, just waiting to take us over, body and soul.

The way that furnace heat rushed up into us when we stirred that

razor grass, sometimes I felt like the devil himself was grabbing

us by the balls. So you knocked some teeth out. There were guys

who were cutting and shooting off men's .... But Tojo Junior

didn't suffer much. I was assisting as your anesthesiologist that

afternoon. One shot from my .45 in his temple and he cheerfully

fulfilled his duty to Hirohito."

His father shook his head. "Some nights when I wake up, his face

changes under me – first those slant-eyes, then the nose,

and the mouth. He becomes my boy Pete, choking to death in that

iron lung, with his eyes all rolled back and scared, pleading

with me to do something, and I'm trying to save him with my hands

in his mouth, but there ain't nothing I can do for him. For one

minute, when he was lying there all scared and struggling and

choking, I wanted to cradle his head in my hand and take out my

.38 and ... Jesus, my son, my son, my own fucking son, and all I

could have done to take his suffering away was blow his goddamned

brains out. Mister Big in heaven sure cooked up a way of paying

me back in spades – right in the here and now. I ain't

gotta wait till they shovel dirt in my face for my taste of

Hell."

Altar boy Latin played in the boy's head: Absolvo te tuis

peccatis, "I absolve thee from thy sins," and he moved away

from the confessional screen. "Say three Hail Marys and

an Our Father and sin no more." That was penance?

Christ, he'd never think so again. He came toward the table.

There were four glasses there, all more than half full. He walked

deliberately over and drained them, one by one. After a while, he

felt some pretzels cavorting in a bubble bath in his stomach and

a-hankering to make a return trip up his gullet.

He picked up a glass and stared at the figure whose lips now

seemed drawn back in a leer, like the lips of Frannie Bouchard

who ran a business in the carriage house behind her house. The

teenagers called it making boys into men, and, when he was eight,

they'd given him a nickel and sent him off for a complete job.

Decked out in a yellow-and-blue striped polo shirt and shorts, he

knocked on her door. He cracked an Atomic Fireball

between his teeth and pushed back an old Army cap as the door

swung open. He repeated the words the teenagers had taught him.

"Hi ya, sister. I'm here for the works and I got dough." She

stood there in a ratty yellow chenille bathrobe with one hand on

her hip. The robe looked like she'd spilt a nine-course dinner on

it, and there was a musty stale smell about her – not the

neighborhood smell, but like what comes up out of a hole if

you're digging dirt for worms. She brushed back her hair which

hung straight down over half her face, like Veronica Lake's. But

this dame was no movie star. She leered out of

Coke-bottle glasses that barely covered a large dark

mole over her

left eye. A fancy orange marbleized cigarette holder projected

from a set of teeth that were the spitting image of a yellow

picket fence a coal truck had crashed through. She looked like

FDR in a woman's get-up.

"How much dough you got, piss-ass?" And he said, "A nickel." And

she laughed and said, "You think I'm running a penny-candy store

here, kid? That ain't enough to get your foot in the door.

Amscray, buster." And she had snickered and waved her holder at

him as he hauled his Radio Flyer down the cinder ash driveway,

with his face as red as his wagon, thinking it was easier to

become a man by killing people, like his father did. Maybe he'd

start with those teenagers who had tricked him.

But now, there in the kitchen, as he stared at the empty glasses,

the tassels were a-twirling. Oh Lordy, yes, they were a-twirling

and a-swirling, and a-whirling, like the red, white, and blue

pin-wheels he had hooked to his bike handles when the Korean War

ended. He could almost hear the flapping again and feel the wind

streaming through his hair when he went up and down the street

yelling, "The War's over, it's over."

He just bet Frannie had tassels on her diddies too, but he wasn't

gonna find out in this lifetime, the way he spent his nickels on

Atomic Fireballs. So like his father he'd have to become

a man some day by getting in a war and killing somebody. That

wouldn't cost a red cent. And that Frannie babe – a guy'd

probably have to spend a month in a claw-footed bathtub up to his

neck in bubble bath after she got her biscuit snatchers on him.

Behind him the screen door slammed. He turned to his uncle.

"Where is Dad?"

"Taking a stroll down by the river." The boy was surprised at how

uncontracted and precise his own diction was, not like drunks' in

movies. His uncle smiled and said, "You've been tin-earing, ain't

you?"

"Yes. Yes indeed I have." Christ, he was talking like a book,

like Howard Pyle's version of King Arthur, and when a

little shit like him started talking like that – well his

uncle was no fool.

"They're twirling, aren't they boy? You've been to Jericho, ain't

you?"

"You can take that to the bank and cash it, uncle Pete. Yessiree

Bob. They are and I have. And the whole kitchen is in on the

action."

"Sometimes, kid, it ain't such a bright idea, tin-earing on other

people's conversations."

The boy revolved a glass on the table. "Uncle Pete, a few weeks

ago, we were out to the cemetery putting flowers on Bridget's

grave. And Dad told me she had been one fine sister." He burped.

The pretzels stayed down. "But when we passed by Grandpa's, he

spit on it when he thought I wasn't looking. But I caught him and

asked him, 'Why you spitting, Dad?' And he said, 'I'm doing him a

favor, boy. His ass is burning in Hell and I just cooled him down

for a spell.'"

"Your Grandpa used to give boxing lessons too, back when your Dad

was a boy, but not so Mike could defend himself against a bully.

When he got liquored up, he got mean. And when he got mean, he

took Mike out to the shed supposedly to help him clean things up.

Then he'd look for an excuse to lay into him. Maybe Mike'd drop

some old screwdriver that looked like it had spent the last ten

years parked up a horse's ass. Suddenly Pa'd set to raving that

was the best screwdriver he ever had. Jesus, you'd think it had

been handed down through the family from Joseph the Carpenter

himself. 'Gonna have to fix you for that, boy. Fix you so you

never drop one of my tools again.'

"Then he'd set to whacking Mike around. But when Mike turned

twelve, he fought back and slugged Pa in the gut so hard that he

shot his doughnuts all over the shed. 'Clean it up, you little

bastard.' 'Clean up your own swill, Pa. You lay a finger on me

again and I'll take a bat to your head. And Pa ... calling me a

bastard, that's the biggest compliment you ever paid me.' He left

him there crawling in his own vomit, half hoping he'd fall asleep

on his back and choke on it. He never touched Mike again.

"Six years later he enlisted and I joined up right afterwards.

Then one Sunday morning in December 41, thousands of miles away

in that barracks in the Pacific, the War came along .... Oh yeah,

it just strolled right in on us without so much as a howdy-do,

traipsed right in, and knocked us on our asses for four years

– or better, on our stomachs, since we spent those years

crawling like dogs through all that grass, mud, slime and rot.

There were things we did out there ... some we had to ... others,

well it was like something from those jungles got into us.

"Sometimes, kid, when you swallow that much dirt, it takes a

while to spew it all out. And when you do choke it up, it spills

over on other people too, the ones you care most about. Mike

brought the War home with him. It's like he's still playing

jungle scout, trying to find his way through the jungle, looking

for something he lost over there.

"Your Ma – it wasn't just Pete and it wasn't just her. It

was the War too, the way it changed your father. She loved him as

much as any woman loves a man. But she couldn't handle the way he

changed – the moodiness, the nightmares. There's a side to

Mike .... She took after you because you were so much like him.

She wouldn't have dared pull that shit on Mike. He would have

taken his Kabar and .... And you, Mister Tough Guy,

trying to keep the family together, too proud to tell him what

was going on. Jesus, how many times could you fall off that

piece-of-shit bike of yours?"

The boy grinned and looked down. "Dad used to say if I kept it

up, he'd have to put the training-wheels back on. And wouldn't I

look like one, delivering papers like that. Uncle Pete, why did

he keep the tooth?"

"You remember Mac, married Bridget. Bad alcoholic, but he always

kept a bottle of Old Crow in the cabinet over his sink.

Reminded him of what he had been and what he was never going to

be again. Used to quote that poem we learned in school by Edgar

Allan Poe. He'd swing the door open, look at the blackbird, and

say Nevermore. That tooth was your Pa's way of saying,

Never again. Your Pa's a tough guy, but you and he are

alike in a lot of ways – thinkers, brooders, always trying

to piece things together, connect the dots.

"I was like that when I was a kid. When I was eight, I sold forty

jars of hair pomade and got me a BB-rifle for a premium. Went out

in the fields and started shooting every can, bottle and branch

around. Then a sparrow came into my sights, and without thinking,

I dropped him – crippled him bad in the wing. I took him

home, laid him under the shed in the back where Pa made panther

piss. For two days, I fed him crackers and water, then he cashed

in his chips.

"He suffered, and I knew I should have finished him off right

away. But I kept him alive, for myself, as though what I had lost

when I shot him, I could still recover, as long as he was alive.

It was like that bird and I were kin, part of each other.

"The night he died, I went out behind the shed where there was a

rain barrel. And when I peered in, there were stars reflected in

that still dark circle of water. I cupped my hands and drank,

trying to put one of them stars or something from up there,

something divine, back into me, into my soul. Crazy little Mick

Catholic. I was looking back, trying to right what couldn't be

righted. I'd never killed anything before.

"Pa and the War taught me to sort things out in my head, shut

doors in my mind. That kid whose brains I blew out – that's

over for me. If I think about it, I can hear the blast of my .45,

feel the gun's recoil against my hand, and the bits of him

splattering into my face.

"But I don't dream about it. I don't search for meaning where

none can be found. It was them or us out there – and us,

well, we came home. Mike ain't like that. He's always opening

doors, looking back. You're cut that way too. Life ain't gonna be

easy for either of you. Some day you'll be sixty years old and

still thinking back to these times – maybe to this very

night – and wondering how you got from point A to point D,

revolving and recreating scenes in your mind. You ain't never

gonna put an end to it. The day they shovel dirt in your face,

you'll still be hearing the old voices and music in your head.

And maybe you'll find meaning there, but more'n likely you won't.

"Now you'd better get your ass up to bed. You look like a hophead

who spent a night on the rainbow. If Mike comes home and smells

that breath of yours, you're gonna be walking funny for a week.

He drew a roll of mints out of his pockets and handed them to the

boy.

At the hallway door, the boy turned back and said, "The War,

uncle Pete, it wasn't like in the movies?"

His uncle laughed. "Jesus, kid, do Mike and I look like John

Wayne and Robert Taylor? We were just ordinary Joes doing a job,

trying not to get our asses shot off, trying not to piss our

pants while doing it. We went into the dark, and we found out

things about ourselves we never knew – some good, some bad.

"I hope to hell you never have to find that out the way Mike and

I did. You've had some tough breaks yourself already. You've been

throwing boxcars for a while now. But poking around in the dark

corners, dancing with skeletons, when you're young – well

sometimes, the skeletons stay with you, and you can draw on those

little two-steps later in life. Having some hardness in your life

when you're a kid, getting some dirt on you – sometimes

that ain't the worse thing in the world. You came from folks like

that, straight out of the Irish potato patch. You're gonna be ok.

You've got something the rest of us never had – a gift of

words. Maybe you'll take another path out of this neighborhood.

But don't you ever forget where you came from. That'll be

something you can fall back on later, no matter what happens to

you."

"I'm glad Dad named Pete after you. Sometimes it's like ...."

His uncle coughed. "Jesus, don't get drippy on me, kid. We're

both corked and any minute you'll have us doing Joe and Ernie

impersonations, like a pair of sob sisters chanteusing an onion

ballad. I know. I know. Now get your ass up those stairs and

start sucking mints. And, Numbnuts, don't fall asleep with one in

that fool kisser of yours and choke."

The following Monday afternoon, the boy walked home late from

school. He had arrived there that morning just after Mary Ellen

White had pealed the bell on the porch, and, when he came up the

steps, she grinned the snitcher's smile and scurried off to tell

Sister. Sister kept him after and made him clap all the dust out

of the chalk erasers and wash down the blackboards.

Large elm trees lined the sidewalk on his way home. Ahead he saw

one marked with an X. It was dying. He knew that for a fact. The

day before, he passed by a shabby old gent marking it. He looked

like one of the hoboes who hung around Water Street who

supposedly kidnapped kids, ran off with them on the rails and

turned them into bindle-boys, He wasn't certain what bindling

was, but intuitively he felt it was something he wanted no part

of. The old guy was stooped over and his left leg trailed his

right. His slouch-brim's sweatband was stained and his green work

shirt marked with oil and ink. His red-spidered nose looked like

a road map to every gin-joint within a fifty-mile radius.

"What you doing that for, Mister?"

"Tree's dying, got the Dutch elm disease. Funny kind of blight.

First showed up during the Depression when a lot of things were

kicking in – factories, farms, men's dreams, and then one

day the elms just decided to cash in too. Someday all these

trees'll be gone."

"It don't look like it's ailing."

"You have to know how to read the signs, boy. See those branches,

high up in the crown, how their leaves are curled and yellow and

some are even brown, like somebody went right up there and parked

his keister and shat on them. That's a sign called flagging. Got

a pocket knife?"

The boy handed him his Budweiser knife with the chipped

pearl handle. The old guy nicked the tree and tore away the bark

like a scab. Underneath, the tree's white wood was striped with

brown. "That's the fungus, boy. This tree's all infected. Gotta

come down or it'll infect all the other trees."

The boy pressed his hand against the fungus and felt the tree's

vessels that conducted water and now death upwards. "My old man

was in the War, in the Pacific, got himself some jungle rot on

his toe that looks like this shit. Were you in the War, mister?"

"Me? I was too old. Had a son over there, though."

"Did he get jungle rot?"

"Yes, yes he did and a piece of shrapnel too, right under his

arm."

"My own man picked up some shrapnel. They fixed him up. Did they

patch your kid up too?"

"Couldn't. Piece of metal went right on through and pierced his

pump. He's still over there, buried somewhere on one of those

islands. They say they're gonna bring all the boys home some day,

but I dunno, I dunno."

"My brother died, but not in the War. The polio got him. I knew

people died, but I thought trees just went on and on."

"Everything dies, kid. But there's a trick with trees. When a man

dies, sometimes they stick him in the ground so fast no body

rightly remembers where they laid him. But trees – well

they can be dead a long spell and still stand up – until a

wind storm comes round and knocks them over and then you know

they've been dead a long while. Sometimes I think there're men

that died in the War who're still walking around, not knowing

they're dead. But trees just abide a little longer than other

things." His calloused hands pressed the wood of tree as though

he were trying to force the poison out. Then he turned and smiled

at the boy. 'OK, buster, put an egg on your shoe and beat it. I

gotta finish up here."

There it was, the dying tree with its red X. And somehow the boy

knew there was trouble behind it. It was hot that day, and he

stooped in the road and picked up a small ball of melted tar to

chew. A gasoline taste flooded his mouth. He glanced at the tree

again. Sure enough Sean jumped out. "How's my favorite punching

bag?" The boy went into a fighting stance. "Learned a few tricks

since last time. That's just fine. Beating the shit out of you

was getting to be a drag."

As Sean came at him, the boy spat the ball of tar into his

broad-planed face. Sean wiped the tar and drool off. "You little

–" Before he could finish, the boy shot his right knee into

Sean's groin. The blood drained from Sean's face, and his lips

formed a perfect geometric circle as he doubled over. But the

circle became a narrow rectangle as the boy whirled a right hook

into it. He collapsed on the cement sidewalk. It wasn't like in

the movies. The boy's hand throbbed and bled all over from a gash

furrowed out by Sean's decayed buckteeth.

Then he saw his god up the street on the porch – his old

man leaning over the railings and grinning. Grinning? Jesus. If

some guy had come along and rammed a lit candle up Daddy Jack O'

Lantern's ass, all the little kids in the neighborhood would have

been out on the button and running up and down the street,

yelling, "Trick or treat." The great Tiki from the far Pacific

was pleased; the devil god was getting his human sacrifice. The

kid felt like Boy in a cornball Tarzan movie, only in a

Polynesian setting, and the drums of sacrifice were pounding

through the jungle. "Serve the mighty Tiki, serve the

all-powerful Tiki."

For a few seconds, he hesitated. Sean's was curled up and

squealing, squealing like Spankie that day in the kitchen. His

tattered blue work shirt had come out of his waist, and there

were purplish bruises on his back – probably his old man's

handiwork – and to the boy's surprise the bones in his rib

cage seemed to stick out. He glanced up the street. His father

moved his finger across his throat. Carotid time.

Remorse, compassion, faith, hope and charity, the Golden Rule,

saving pagan babies – zippo, all gone. Praying for the

conversion of Russia – forget that. Just drop the Big One

on the Red bastards. Now the rage was on him. He was a berserk,

in service to the devil god. He aimed his right foot just below

the rib cage and struck. Sean's body jerked like that time in

school Patty Jordan had gone into an epileptic fit in the

hallway.

Then the kid danced around him and fished into his pocket. No

piano wire, just string from a yo-yo. He dangled the string

before Sean. "Next time, no more Mister Nice Guy. You come for me

again, I'll wrap this string around part of you – I ain't

saying which – but you'll be walking funny for a year. You

just thank your lucky stars you ain't get no gold in those rotten

teeth of yours, buster, because you'd be looking up at the last

of the '49ers. California, here we come. Who knows what evil

lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows and that's who I am,

the fucking Shadow, come for your sorry Commie ass."

From some small, objective vantage point in his mind, a lonely

islet, not yet submerged in the waters of the Pacific, he heard a

tiny voice saying, "Time to be playing with the squirrels, buddy.

Next stop, the Cackle Factory and, boy, ain't you gonna be a

stylish number with those shock-treatment electrodes hooked up to

your temples." He left Sean there, curled in the fetal position

beneath the elm with the X on it.

That night, his father took him out to Phil's diner. Ordered him

up two cheeseburgers, pile of fries, a huge Coke and a

banana split. Told everybody within earshot how his kid took care

of business that day. "He's your kid all right, Mike." "If he'd

been over there, we would have come back in '44." "Should have

sent him to Korea, Mike. He and Old Doug would have swum across

the Yalu river with their Kabars in their teeth." Mabel,

the waitress, snapped her Chiclets at him, refilled his

Coke and addressed him as Mister Rock'em Sock'em. That

was him all right, his father's son, the black-tongued killer

spawn of great Tiki, fresh from the lava pits of

Beserkdom. His uncle Pete sat beside him with his

Howdy Doody grin. Every now and then he'd put his arm

around the boy's shoulders but he said nothing. Howdy

knew the score. In that little group, he was Albert Einstein

sitting in the Peanut Gallery. Pete's eyes tried to lock onto

Mike's, but, for some reason, Mike was always looking in the

opposite direction.

Afterwards, the boy retired early, complaining of a stomachache.

In his bed, he kept hearing that squealing sound Sean made on the

ground, just like the loose fan belt on their rusted-out '36

Plymouth or a piglet who's about to become sausage. He wondered

if Sean made that sound when his old man was beating on him. When

someone was always knocking you around, after a while, you wanted

to give some too. Christ, he knew that, should have known that.

He had enjoyed giving it, feeling Sean crumple to the ground

under his fists and squirm as he kicked him. But why the hell did

he have to kick Sean after he was down, after he saw those

bruises on him? Those purple loop marks – he'd seen them

plenty himself, just like the hand impressions. It must have hurt

like hell getting kicked on those belt bruises. Why had he done

it? As he stared at the ceiling, spider-webbed with cracks,

specks formed in his eyes that became dots – dots to be

connected.

It was as though a surge of electricity had passed through him,

as if the pain and anger he had held in so long flowed into that

crumpled form. He clenched his fists, slugged the broken-down

mattress and rocked himself against the footboard. He drifted

back three weeks.

Glass shattered in his head, wood splintered – the panes

and mullions of cellar windows – and he recalled his rage

following the rock down deep into the dark cellars. His body

convexed in the bed when he felt that release again. The wobbly

footboard became the pebbled muck that bordered the foundation of

neighborhood houses and sucked at his frayed Jeepers. On his

street, the rain fell hard off the drainless tin roofs, not down

through spouts and drains like on the fancy houses on Mansion

Avenue. That sucking sound – he'd heard that before too

– outside Pete's room in the hospital, the room they

wouldn't let him in.

At first he had just followed after his pal Frankie and watched.

But one night, Frankie had turned and said to him, "Some times

when the moon or the street lights are just right, I see yellow

Jap faces in the windows, the Japs who snuffed my own man on Iwo

Jima while he was trying to dig his hole in that damn ash. And

when the glass explodes, I feel good all over because I pretend

Dad came home and we ain't living in that shit-ass trailer park

and Ma ain't cleaning toilets at night in the office buildings

downtown.

One evening, the light rippled in the bubbled glass and played

just right for him, and he held Frankie's arm. "My turn."

"You see 'em too?"

"No. Something else."

And Frankie just smiled, spat on the rock, and handed it to him.

"Give her a good one – smack dab in the kisser."

He passed Nick's tavern on the way home, and there in the window

was the familiar neon sign that blinked red for wine and

green for beer. But this night, as he lay in bed

remembering, the letters changed, and the sign blinked out a red

hate, a green need. He hated her. He needed

her. He hated her because he needed her.

Something clicked in his head. The first dots joined together.

Then he recalled two days later. Frankie was helping him with his

paper route and old McCreary came to the door and said. "Well, if

ain't Ragged Dick and his sidekick Ibrett." And the boy said,

"Why you calling Frankie Ibrett?" And McCreary leaned down and

said, "Short for Inbred Trailer Trash." The boy clenched

his fists, thought of his first afternoon in Frankie's oven-like,

rusted-out Airstream trailer when his new pal showed him his old

man's medals. "Ain't nothing more prideful than having your

father's medals. Your old man was A-1, Frankie." And Frankie

smiled and said. "Yours is too." Then Frankie passed him a

piss-warm flat Coke that was sitting on the countertop

near

some oil rags Frankie was using to fix the icebox. The boy drank

half and passed it back to Frankie who finished it. That was the

best tasting Coke he ever had.

So when McCreary spewed out his insult, the boy clenched his

fists, but then just grinned and said, "You're a real funny guy,

Mister McCreary. Ain't he, Frankie?" Frankie shoved a mass of

thick jet-black hair out of his eyes, the shape now of two slits,

and said, "Yeah, he's a real hoot." The last time he saw

Frankie's eyes that shape, he had told him how Sean was laying

for him. And Frankie had said, "A vet down at the park is

teaching me to shoot his .45. I reckon he'd let me borrow it. I

seen what it does to cans, and I reckon it would blow a hole

through Sean's face a cat could jump through. The boy thanked him

for the idea, said he liked cat tricks as much as the next guy,

but maybe that was a solution they could work up to,

gradual-like. Jesus.

As they came down the steps, they exchanged a glance. McCreary

had unwittingly just signed a contract for some home improvements

– cross-ventilation in his basement – custom work.

But that night, McCreary was in the basement changing a fuse when

two rocks blitzed through, one an inch from his head. Nearly

killed him. He yelled after them he was going to make some phone

calls right quick.

The boy remembered how he ran all the way home, came up the

steps, gasping for air, and lingered on the porch before the

screen. Inside, Philip Marlowe with his slouch-brim, white shirt,

tie and shoulder holster was playing solitaire at the table.

Twenty-eight cards arranged in a triangle –

Pyramid, a game his grandmother had taught him one long

boozey afternoon. Six props surrounded the triangular tableau

– the dealt hand, the waste pile, a bottle of Jack

Daniels with glass, a badge, and the razor strap.

God, he had a classy old man. Joey's LaDuke's dad would have been

standing at the door in a beer-stained tanktop, with his paunch

hanging out, holding the belt and ready to grab him by the scruff

of the neck as soon as he came in. And Tommie Mcginn's dad

– geez, that Bozo wouldn't even have a shirt on.

Baldie'd be running up and down the street waving the belt,

cursing and yelling, "Toooomeeeee!" Sure, sure he was going to

get his ass whipped off, but at least it would be done with a

sense of style and dignity. Mike was the Iceman and the Iceman's

son was going to get iced.

A cool breeze from the river passed through him, and, for a

moment, he shuddered at the thought that he had lost something

again. He stared through the screen, scanning the individual

quadrants, as though trying to imprint in his mind an indelible

photographic image of what was about to pass away. He felt lonely

for his father, wanted to have grown up with him during the

Depression, been in the War with him. He knew well what he had

done out in the streets now separated him from Mike, and Mike was

the only family he had left. He felt like Adam, looking wistfully

back into the Garden and seeing God playing solitaire.

He entered, slammed the screen. The Iceman didn't flinch. He came

behind him, put one hand on his shoulder, and examined the

pyramid. He reached into the bottom row and discarded into the

waste pile a king, value thirteen. Silence. He reached again for

a nine of spades and a four of clubs to discard. Mike hand's

circled his wrist. "My game, kid. By the way, Mister McCreary

called while you were out for a stroll."

"Yeah? What'd that old geezer want? Ma's three-bean casserole

recipe?"

"Bingo, kid. Bingo. Funny the way a guy gets a hankering like

that at 2:00 in the morning. Good thing, though. Seems he caught

two yeggs smashing his cellar windows."

"Dad, I –" His father's hand came up from the table and

knocked him on his ass. Not hard. Just enough to get his

attention – the kind of smack Spankie would have

appreciated. "Ain't you heard, kid? Night air ain't good for your

health." Then the hand jerked him up near the table, picked up

the badge, and the hand's owner said, "Spit on it."

"No, Dad! I ain't –"

"You don't get it, kid. What you did out there ... you already

spit on this buzzer. Two things I care most about, this badge and

you, getting you out of this shit-ass neighborhood into a better

life than I ever had. And now tonight ... Back in the Depression,

after Pa's wages got cut and he came home and cried, I took my

BB-gun and shot half the cellar windows out on Mansion Avenue,

just to show those swells. But you, you're James Dean, Mister

Rebel Without a Cause. Christ, most of the guys down here work

sixty hours a week just to keep a tin roof over their shacks. And

you break their windows? He held the badge up again. "Spit on it

or I'll ram it down your throat and out your ass." His voice was

level, without emphasis.

The boy's mouth felt like somebody had shoved a hair dryer into

it, but he summoned up just enough drool to manage a spit.

His father returned the badge to the table, into the waste pile.

The boy had expected a B-crime movie scenario, but tonight High

Theatre was on the bill.

"In the islands, some nights were so dark you couldn't see your

own hands. We lay in slit trenches on our stomachs holding our

Kabars, waiting for the Japs to sneak round and jump us.

You had to listen real careful, and when he made his leap you

whirled round and stuck him right in the gizzard, right when he

was jumping you. When you let the air out of a man and he's

dying, his muscles spasm, his face twitches and sometimes there's

a funny choking sound, a rattle in his throat. If he's lying on

top of you, you feel death and him struggling. Sometimes at the

end, he even pisses on you. Lots of guys breathed that rattle

into my ear before they died. Jesus, sometimes their lips were

right up against my ear, as if they wanted me to know what they

were seeing on the other side. And every time they whispered and

that rattle settled in my ear, something inside me died too.

Something decent.

"All the time I was out there I kept thinking about a white spot

inside of me that none of that filth and shit could touch. That's

where I kept my dreams for after the War, the way a woman keeps a

hope chest. I'd come back to this shit-ass neighborhood, carry a

badge, raise some kids decent, send them out of here to make some

difference in the world. Back in the Depression, a lot of people

saw Regular Army guys like us from places like this as dirt. We

weren't the Marines or even the Navy. If we died, what difference

would it make? We never would have amounted to anything anyway.

Maybe a toilet wouldn't get cleaned, a pot-hole filled, a floor

swept, a car greased, or more likely, jacked. No cures for cancer

here, no great books, no inventions. Just Regular low-class Army

trash. I wanted to prove them wrong.

"Your brother already left this neighborhood decent, not quite

the way I planned. But if being in a box is the only way for you

too, ok, I'll be master of ceremonies at your cold meat party.

You want to be James Dean? I'll get you a little red jacket just

like he had in the movie. You can run around the kitchen, hold

your head in your hands, and yell, "You're tearing me apart,

you're tearing me apaaaaaaaaart!" I'll sit here, nurse my drink,

play cards, listen. Jesus if you want, I'll even let you sit on

my lap and tell Daddy all your troubles. But when you've said

your piece, boy, I gonna do you. I gonna do you good. Rules of

the shop.

"You got me confused with Doctor Spock. Big mistake. I'm Doctor

Spook. Make you a deal, though. Tell me why you did it, and maybe

in a week or two, you'll be able to pass a window without shaking

or drink out of a glass cup again. But if you don't, you're gonna

be drinking out of paper cups till you're eighty years old."

The kid's knees knocked together. He was the son of the Priest.

That's what they called Mike down at the station. If some mug

didn't feel like talking, the other cops always said, "Send him

to Father Mike. After he talks to the Priest, he'll confess.

Jesus, he'll be telling us about the first piece of penny-candy

he stole when he was five."

So the son of the Priest was scared, Her face forming, shifting,

and then exploding in the window, flashed in his head. It would

be easy to tell. But there was something else inside of him too,

stubborn, hard like the steel shrapnel in his father's arm,

something that was his father's and his too. The way he felt

about her was private, not to be shared, whatever the

consequences.

An old phrase from that other war came into his mind –

Belleau Wood, the gunnery sergeant trying to knock the fear out

of his men. "Come on you sons of bitches! Do you want to live

forever?" And his second self – the one apart from the son

of the Priest – the little son of a bitch – genuine,

card-carrying and bottle-fed – looked directly at his

father and said, "What do you think? I want to live forever?"

Something came into his father's eyes, like at first he couldn't

quite figure. But then he smiled and said, "No, Sergeant Daly, no

son of a bitch in his right mind would wish that on himself."

Grim again, he focused his eyes on the tableau. "What's the

object of this game?"

The boy rested his hand on the tableau. "To clear away all the

cards in the pyramid by the time the hand is played out."

"And if you don't ..."

"Game is lost. No re-deal."

"Exactly. I'm clearing cards, boy ... and accounts. Call it."

He locked eyes with his father. His knees were still knocking,

but he just said, "Those plastic cups Grannie gave me when I was

a baby, the ones with the yellow duckies on them – we still

got them?"

And his father, looking old and tired, said, "You're a hoot,

kid."

"Yeah. That's me all right. I'm a triple scream and a yell."

"Boy, you hit that one on the head." He picked up the strap and

pointed down the hall to the spare bedroom. "Next time, Al

Capone, don't leave witnesses."

All that was three weeks ago, and the boy lay there now,

remembering, sorting it out in his mind. Then he heard a second

click. Hate, need flashed again. He hated

himself because he needed himself. And when he kicked Sean, he

lost himself. It was sounding like a nursery rhyme –

Jack and Jill went up the hill – but in his

condition that's what he could come up with. He had taken on his

father's hatred, and he knew why now – to rid himself of