One Helluva Woman

War Correspondent Dickey Chapelle with U.S. Marines

Georgette Louise Meyer was born to German-American parents

in Milwaukee Wisconsin in 1919. Her family was not wealthy, but

solidly middle class, and suffered very little economic hardship

during the Great Depression.

"Georgie Lou" was, in the parlance of the day, a "tomboy",

mainly due to the influence of her father who instilled in her a

love of adventure and the belief that a woman could do anything a

man could do. Most of Georgie Lou's heroes were men, especially

Admiral Richard Byrd, so much a hero in fact that during her teen

years she took to calling herself Dick, which soon became Dickie.

To say that Dickie Meyer went against the grain would be an

understatement. One young man who finally got up the nerve to ask

this aggressive female out, reported his experience. "When I went

to pick her up, I presented her a corsage. She took the flowers

but then walked over to my car and said, 'how fast does this baby

go.'" The boy went on to say that "the date went well but it felt

a little strange because I'd never dated a girl with a crew cut

before."

Dickie was a fine student who often argued with her teachers

and was usually right. She was class Valedictorian and this honor

along with help from a family friend earned her a scholarship to

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where it didn't take

her long to flunk out, mainly because she didn't like to attend

class. Most of her class cutting time was spent at the local

airport watching planes take off and land. When she wrangled a

trip with a pilot who was delivering supplies to flood victims,

she became immediately hooked. She also spent a lot of time at

the local Coast Guard base and was so impressed she wrote a story

about her visit and sold it to a local publication for seven

dollars and fifty cents. While she showed and aptitude for

writing, she told her mother she could never be a writer because

it didn't pay enough.

She returned to Milwaukee, because, as she said, "it didn't take

long for me to figure out that I wasn't cut out to be an

engineer, and while I once thought I'd like to design airplanes,

I now knew it would be a lot more fun to fly one." No doubt it

was for this reason she approached the flight instructor of the

local air circus with an offer to be his private secretary, in

exchange for flying lessons.

Dickey fit in perfectly with the free spirit types who

inhabited the air field; stunt pilots, wing walkers, and

parachutists; men who looked death in the eye on a regular basis

and wouldn't live any other way. They loved this young girl who

dressed like a boy, wore her hair short, and had a deep voice,

like a man. She never became a good pilot like them, but that

didn't matter, she was part of the gang. If Dickey took anything

away from her flying circus experience, it was that she wasn't

cut out to be in any office. She needed action and plenty of it.

But if Dickey dressed like a man and talked like a man, she

was definitely all girl, and when her parents found out that some

of the action she was getting at the airfield had nothing to do

with flying, they shipped her off to live with her grandparents

in Coral Gables Florida. What they didn't know was that the

grandparents home was just a few miles away from the oldest and

largest air show in the country.

Dickey could write, and she could type, and she quickly landed

a job as a publicist. Her grandfather initially resisted, knowing

of her experience in Wisconsin, but when he realized it was a

real job he grudgingly assented.

Dickey didn't know it but she was about to begin her career

as a reporter.

Her boss in Florida sent her to cover an air show in Havana,

Cuba, with instructions to file as many air show stories as

possible with the Havana bureaus of the Associated Press and the

New York Times. Dickey was ecstatic. She was now

(theoretically at least) working for the New York

Times. She was also about to learn some valuable lessons

about reporting.

As sometimes happened at air shows, there was a horrible

crash that took the life of the pilot. Shocked at the first

horror she'd witnessed, Dickey was momentarily unable to act.

Then, she realized this was a story and she needed to be on the

phone reporting the incident. A reporter from another publication

connected her with the Havana bureau of the

Times when Dickey couldn't find the number in

her handbag, explaining that he didn't mind since he'd already

scooped her. Dickey had learned very quickly that reporting was a

cut throat business and one had to be tough and talented to

survive. It was a lesson that would serve her well in the years

to come; and this incident, which got her adrenaline pumping,

also told her what her life's work would be, since her bungled

attempt at reporting nevertheless got the attention of the

Aviation Editor for United Press. Her official title was

secretary but the job landed her in New York City, the hub of

everything. And she landed there on the eve of World War Two.

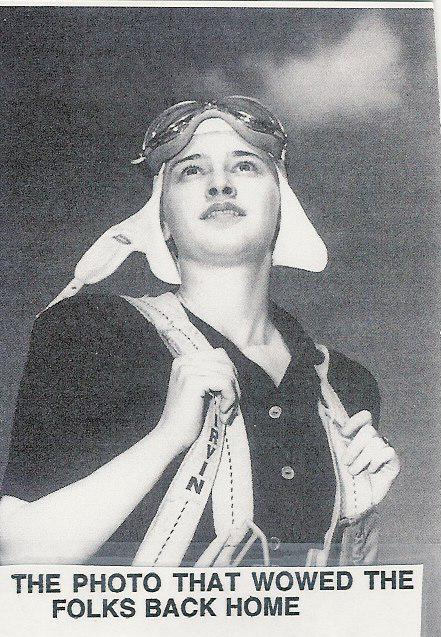

It was here that Dickey met Tony Chapelle, a pilot and

photography instructor when she signed on as one of his students.

Tony was twenty years older than Dickey and a man of the world.

It was he who took the now famous photo of Dickey, dressed in

pilot's gear, wearing a parachute and looking skyward. Even

dressed as she was, it's the photo of a voluptuous young woman

who makes Amelia Earhardt look like a boy.

When the photo appeared in a Milwaukee paper, the home folks

were amazed. Could this be the dowdy, overweight young girl who

never looked or even acted feminine? Some of these same folks

must have inhaled deeply when gazing on that photo, and thought

– you've come a long way baby.

By this time Dickey was madly in love with Tony; so maybe

she was beautiful because he told her she was. She became his

creation. He changed her glasses, her wardrobe and her attitude

– she now saw herself as a desirable woman in addition to a

strong willed one.

By the time of their marriage, in Milwaukee on 2 October

1940, her family was also captivated. Despite the fact that Tony

was Dickey's senior by twenty years, not very handsome at five

feet seven and two-hundred pounds, the family decided he was a

good catch, and just the one to reign in Dickey's impetuousness.

What they didn't see was Tony's violent temper or his penchant

for lying. The marriage to their daughter and sister wasn't even

legal. Tony Chapelle already had a wife he'd forgotten to

divorce.

But there can be no doubt that Tony is the most important

person in Dickey's life. It was he who made her a photographer

and taught her how to go after a story and how important it is to

get their first. But the better Dickey got at her job, the more

Tony's insecurities surfaced, and would lead to their separation

and the annulment of their marriage; though Tony would always be

part of Dickey's life.

At the time of Tony and Dickey's marriage, the field of

photojournalism was pretty much a man's domain. The only

prominent female was Margaret Bourke-White of

Life magazine. But with Tony's help and her own

determination and ambition, Dickey began the long hard road of

establishing herself. Her photos never equaled White's, but her

willingness to go in harm's way, any where, any time, set her

apart from not only White but many of her male colleagues. It's

for this reason that no reporter of her time understood the

American fighting man more, or loved him more, than Dickey

Chapelle.

With Tony's help, Dickey's first big success came when she

sold a story to the New York Times about

American pilots enlisting in the Canadian Air force to fight

against Hitler. The story, published on 27 October 1940, billed

Dickey as the first female correspondent having access to

Canadian Air bases.

But there were failures also. Life turned thumbs

down on several stories submitted by Dickie. Bourke-White was

their female star and they didn't need two.

Come December 7, 1941, and the Chapelles, along with one

hundred and forty million others, found themselves in a state of

shock that the dastardly Japs would dare attack the USA. But any

journalist worth his or her salt would see the war as an

opportunity, and for Dickey, opportunity was definitely knocking.

The country had banded together to "lick the hell out of the Jap

bastards", and Dickey was determined to write about and take

photos of that happening. But she was quite unaware of how

American military commanders viewed women reporters at the front.

Look magazine, to which by now Dickey had sold

three stories, gave her an assignment to the Canal Zone, where

she would cover gun crews on freighters running the Japanese

blockade. But Dickey had to get her own credentials, so she soon

found herself on a bus to Washington D.C.

"I presume you know Mrs. Chapelle, that troops in the field

have no facilities for women." These were the first words out of

the mouth of the Army Public Relations Officer, looking directly

at Dickey. "Well sir, I'm sure the Army has solved more difficult

problems than that," replied Dickey. It was an answer Dickey

would use many times and it always got her where she wanted to

go.

Tony, who was already in Panama teaching Navy photographers

how to shoot combat photos had mixed emotions over his young

bride's coming – she was welcome as a wife, but his male

ego took a hit because job-wise, she was now a competitor. And

also, being the obsessive philanderer that he was, he probably

read Dickey's message that she was on the way to join him, from

another woman's bed.

While en route to Panama, Dickey showed her inexperience by

being a major headache for the ship's captain. She began by

throwing film wrappers from her film packs over the side, making

the ship a magnet for German U-Boats. She also committed a major

no-no, by standing on the anchor chain, and was cautioned that if

the line was let go, she would lose both legs. To make matters

worse, Dickey was infuriated to learn that Tony had enlisted his

pilot friends to fly extra missions, so as to insure air cover

for the ship his wife was on. What was Tony doing! Didn't he know

she was an accredited war correspondent, willing to take the same

risk as everyone else!

While doing her story in the Panamanian jungles on an Army

unit known as the Bushmasters, Dickey ran into tons of mud,

mosquitoes, biting fish, and worst of all – Army

censorship. All film and copy had to be approved before it went

out. Dickey would battle military censorship her entire career,

always being frustrated that only part of the truth, the kind

that would boost morale, could be told. War was hell – but

only so much hell would be tolerated by the folks back home

– or so it was thought.

It was in Panama that the Chapelle marriage began to crumble.

While she practically did back flips to please her husband and

avoided stepping on his toes as much as possible; even making

sure she was never paid more than him, and taking the blame (like

many women of the 1940's) for his infidelities. But Dickey had

her dreams, and a will as strong as Tony's. Conflict was

inevitable and things came to a head when Dickey took a photo of

Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox. The flash bulb went off like a

shot. Knox was amused, but not the Secret Service who confronted

Tony about the incident and insisted that Dickey be sent home.

Tony explained that Dickey wasn't there as a wife but as a

reporter. He had no authority over Dickey. The upshot wasthat

Tony, who had accepted the rank of Chief Petty Officer, was the

one being sent home. From their home in the States, Tony waged a

campaign to get Dickey to join him, promising gallons of fresh

milk for his Wisconsinite wife. Dickey came home, but it was

probably due to the fact that she didn't have her story anyway

and was broke, rather than the milk.

Dickey spent the next two years being a dutiful wife and

freelancing for magazines. A normal day's work was two thousand

words.

One of the magazines, Life Story (now

Today's Woman), gave Dickey a lot of work and

hoped she would continue doing "what you're so good at". But

Dickey, who always felt better when her adrenaline was pumping,

had other ideas.

Come February 19, 1945, as the U.S. Marines were landing on

Iwo Jima, and a fully accredited journalist named Dickey Chapelle

was on her way to the Pacific, having convinced her editor at

Life Story, she would bring back some great

stories. The editor, now fully convinced, told her, "I want you

to be sure you're the first woman somewhere, any of those islands

will do." Meanwhile, Tony was in Chungking, China, probably

unhappily so. He couldn't control his little wife from there and

she was getting too big for her britches.

On the plane with Dickey were Navy nurses. They all felt

like strong independent women, above the ordinary; but neither

Dickey nor they had any inkling of the horrors they were about to

face, nor did they realize that many of them would be coming home

in boxes.

The first stop on the trip was Honolulu and when the Public

Relations Officer asked her where she wanted to go, she said, "as

far forward as you'll let me." She meant it.

When Dickey first approached the Admiral in charge of Public

Relations for the entire Pacific fleet about going ashore on Iwo,

she was sternly rebuffed. "The front is no place for a woman." "I

know that sir," said Dickey. "It's no place for a man either, but

no man reporter can tell the mothers, daughters, wives, and

sisters the story of men dying like a woman reporter." She then

added, "I'm going to keep asking." "And I'll keep saying no,"

said the Admiral. But Dickey would find a way.

The Admiral told her she would be assigned to a hospital

ship where she could visit with the wounded and document the

severe need for whole blood. Blood donations coming from the

States were insufficient and all the medical staff were donating

their own blood to meet demand. This put them at risk if wounded

since they'd start a pint low.

Hospital ships were supposed to be immune from attack but

the Japanese enemy didn't abide by the same rules. Dickey would

screw up one more time by not having her telephoto lens on her

camera when she attempted to capture a diving Jap fighter on

film. She could almost hear Tony berating her from New York. The

Chungking assignment had not materialized.

It was while on the hospital ship that Dickey gained a lot

of respect for the Navy corpsman who cared for the wounded while

being in harms way themselves. "These are brave men."

The carnage coming from Iwo was unimaginable. Horribly

mangled bodies, packed every inch of available space. Dickey

tried to retain her objectivity as she shot photo after photo.

But the more personal encounters she had with these magnificent

American fighting men, the more she realized that total

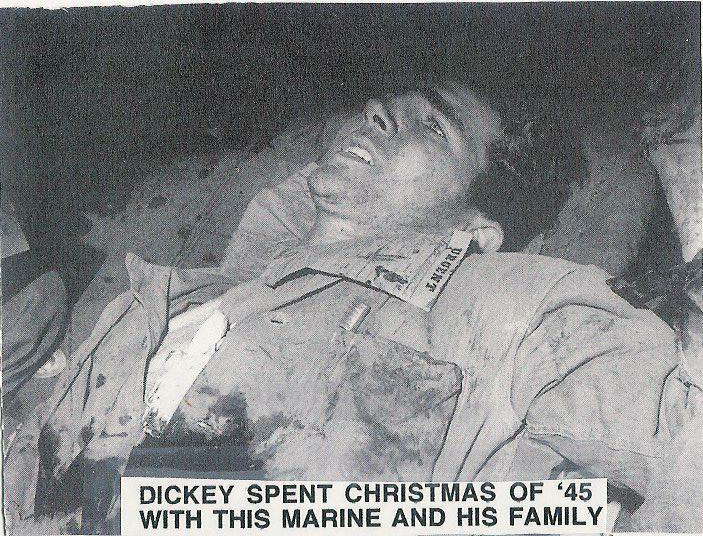

objectivity would be impossible. As she photographed one severely

wounded man, she asked, "Well soldier, how are you?" "Soldier?

I'm a f---ing Marine," he replied in a whisper. Dickey then used

a word she'd never before used in her life. "Well f---ing Marine,

how are you?" The young Marine told her he was lucky because his

buddies had carried him out. He would survive his wound and

Dickey would spend Christmas eve, 1945 with him and his family in

a stateside hospital.

Another unforgettable moment would occur in a field hospital

where she began a conversation with a Marine whose leg was so

badly mangled it would have to be amputated. He told her she was

nuts to walk around unarmed. He gave her his Kabar (a modified

bowie-style trench knife) and showed her how to fasten it to her

web belt. "Now I feel better about you." He said. Dickey walked

out of the tent and cried.

But always in the back of Dickey's mind was getting to the

front. But where is the front and how do I get there? She asked

herself. She walked out of the field hospital and started

climbing one of the sand ridges that seemingly stretched for

miles, where she ran into a Marine Lieutenant. "Can you take me

to the front?" "You want to see the front huh – okay we'll

take you there." Soon she was sitting beside the young officer in

a weapons carrier, headed for the front. She knew she was

disobeying the Admiral's orders but she'd take her chances.

Besides, Dickey Chapelle liked taking chances – the more

the better. As they neared Mount Suribachi, Dickey was awe struck

by the view. Suddenly, the Lieutenant stopped. "This is the

front." Dickey leaped out, walked to the top of a dune and

started shooting pictures. It seemed peaceful enough, except for

the wasps flying around. When she returned to the carrier, the

Lieutenant looked askance at her. "I've never seen anything like

that. Don't you know better than to stand up like that in a

combat area?" "But it seemed so peaceful," Dickey replied,

"except for all the wasps." The Marine laughed uproariously.

"Wasps? Sister, those weren't wasps – they were bullets.

You nearly got your butt shot off!" Dickey wanted to cry, but she

didn't. Instead she said, "I don't think there's anything sweeter

than being yelled at by a handsome Marine."

The next morning as she was headed to the officers tent for

breakfast, a Marine Sergeant took her arm. "You don't have to eat

brass food Dickey, ours is better." As she sat down to the huge

portions, she realized he was right and ate as much as they did.

Later that day the Sergeant asked Dickey to hang his gear on

him as he got ready to go into combat. It was extremely heavy but

he offered no help. As he walked off he yelled back at his

comrades "take care of our girl". Had he said "our girl"?

Dickey's love affair with the United States Marine Corps was now

complete. It was this kind of scene that would have her saying

many times – "When I die I want it to be on patrol with the

United States Marines."

Later, the Admiral who had ordered Dickey to stay out of

combat areas would say that she had a tenaciousness like no one

he'd ever seen.

Come Easter Sunday, 1945, and the Marines landed on Okinawa,

a landing first known for its peacefulness; but would later mean

twelve-thousand dead Marines in four months time.

Despite the objections of Navy brass, Dickey found her way

ashore, just in time for the Kamikaze (divine wind) attacks that

were unleashed by a now desperate Japanese government. When the

Admiral who commanded the Joint Expeditionary Force got wind of

the fact that Dickey – who was described by a male reporter

as "a petite young woman with glasses and a helmet that covered

nearly half her head and who yawned at the strafing planes"

– was ashore, he literally screamed at the Admiral on the

scene to "get that woman out of there!"

But Dickey did not get out. She was there to get a story,

the real story. So she stayed amongst the horror, the blood, the

screams of agony; even holding a lamp while a surgeon operated on

an eighteen year old Marine. And even though she didn't say so,

she stayed for another reason. These were her guys and she'd

leave when they did.

But Dickey did leave, via a landing craft with a young

Marine holding a .45 pistol on her all the way back to the ship.

He had to because Dickey was now a prisoner. The only way the

Navy could get her off Okinawa was to place her under arrest.

Fifty years later, the Admiral who issued the arrest order would

say – "we were fighting a war and she was in the way."

There were a lot of U.S. Marines who no doubt would have

disagreed with the Admiral.

There was even an argument as to how Dickey would return to

the States. The Navy brass wanted her to return via a slow boat,

perhaps hoping it would be torpedoed. A Marine PFC put her name

on a list of those to be flown back. She told him to erase it,

that she didn't want him to get in trouble on her account. "You

rate it," he replied. "What can they do – bust me?"

Tony was shocked at Dickey's appearance when she stepped off

the plane in San Francisco. Her clothing hung on her, she looked

haggard. They tearfully embraced. Then, Tony reached into a

pocket and handed her a letter. It was notification that her

credentials as a War Correspondent had been revoked.

"Well my little bird, I hope you learned something from

this," said Tony. "Oh I did Tony – wait till you see the

pictures."

Dickey and Tony labored long and hard to get her credentials

restored. By war's end they still had not succeeded. The final

straw was her firing by Life Story. She had

submitted her photos for publication and they were quickly

rejected by the editor as "too dirty".

But all was not lost. With Tony's encouragement she

submitted her photos to other magazines. In December of '45,

Cosmopolitan published her photos of wounded

Marines on Okinawa; and while Seventeen would

not publish her photos, they were so impressed they offered her a

job as their only photographer. The Red Cross wasn't offended by

her photos either. Two, of a Marine before and after a blood

transfusion would be used for the next ten years in Red Cross

blood drives.

Dickey and the Admiral who'd yanked her credentials would

later become good friends and he'd later, upon her death, write a

complimentary obituary. But in August of 1945, it looked like

Dickey's days as a War Correspondent were over.

Tony Chapelle would later say that he and Dickey's

relationship was never the same after Dickey returned from

Okinawa. Dickey herself would say that after experiencing war and

being part of such a valiant crusade, a relationship between just

two people didn't seem all that important. But for Tony,

considering his own behavior, to blame Okinawa for the

dissolution of his marriage, seems disingenuous at best.

As the Cold War loomed, Dickey was growing restless in her

job as Staff Photographer and Associate Editor for

Seventeen. She had a steady job but she was

always traveling and this put an additional strain on her

crumbling marriage. Tony would write heartfelt letters expressing

his undying love. Yet she knew that what really bothered him was

the fact that his little bird, his own creation, had flown the

nest and he no longer controlled her. Besides, even though he

expressed loneliness, she knew that Tony Chapelle was seldom

alone.

Another fly in the ointment came when Tony's wife, the one that

he'd forgotten to divorce, charged him with desertion. At this

point he and Dickey had been together for seven years. They would

never be legally married. But then would come the time when

Dickey would realize she still needed Tony. At least she would if

she wanted to work with the Quakers.

The publisher of Seventeen was a Quaker, and she

sent Dickey on an assignment to a Quaker work camp in Kentucky.

Dickey was so impressed with the way the Friends viewed the world

and the way they accepted everyone without question, that when

she found out they were looking for a photographer to go to

Europe and document their Little Marshall Plan, feeding

and clothing the dispossessed of Europe, she immediately

volunteered. But there was a catch. The moralistic Quakers would

never think of sending a lone woman to such a dangerous place.

Her husband would have to go too.

Tony joined Dickey at the camp and soon they were engaged in

a campaign of trying to convince the Public Relations Director of

the Friends Service Committee that they were the couple for the

job. Neither were pacifist, but Tony turned on the charm –

something he was very good at – "just call us the friends

of the Friends". Soon, he and Dickey were on their way to Europe.

Their first stop in their specially outfitted truck was Warsaw,

where the stench of death was everywhere and horror still showed

in the faces of the population.

The six week assignment was soon extended, much to the

chagrin of Tony, who'd come mainly because of his fear of losing

Dickey. Tony had led a licentious life. He was now in his fifties

and paying the price for his careless life style. Dickey was in

her glory and Tony was depressed over "all this damned misery".

But still, they worked well together. They shared the

photography and Dickey did all the writing. Even self centered

Tony could see they were making a difference, and the New

York Herald Tribune did a story on the couple who were

traveling Europe by truck. That same week, the Christian

Science Monitor did a story about "the husband/wife team

who were photographing Europe's misery from 'a white angel

truck'". The New York World Telegram described

Dickey as "a small lively blonde who, together with her husband,

brought back thousands of photographs of Europe's misery". There

can be no doubt that millions of dollars of aid were generated

for Europe's starving masses because of the work of Tony and

Dickey Chapelle.

The Chapelle's sojourn in Europe would last two years. They

even talked their way past the Russians and into Berlin. But

rather than bring them closer they became further alienated.

Tony's constant griping about conditions and his various physical

problems grated on Dickey, and her inattention to her physical

appearance irritated Tony. Others found the couple fascinating

but they were unaware of the tension behind the scenes. Tony

yearned to return to his cosmopolitan New York life, which by now

Dickey found completely shallow.

They returned to New York practically broke, though Tony

through honest and barely honest endeavors kept them afloat. By

1950, Dickey found her photos of Europe's suffering had no

market. Americans were dying in Korea, and suffering Europeans,

many now behind the Iron Curtain, held little interest. Dickey

was further frustrated because no magazine had any interest in

sending her to Korea, and she had no standing with the military

since they had not renewed her credentials.

During the next five years, Dickey and Tony held a variety

of positions, some together and some independent of each other.

One position which they held as a couple was as employees of

Harry Truman's Point Four Program, a plan of aid to undeveloped

countries. The program as viewed by the idealistic Dickey, was "a

bright light in a world grown dark with the Cold War". However,

due to the reality of the Cold War, the Plan soon came to have

strings attached – aid in exchange for mutual defense

commitments. Tony loved the Point Four program as it allowed him

to live the opulent life style in the finest hotels in the world;

from where they would venture out to cover a story about Point

Four technicians building bridges and school houses, or digging

wells and eradicating locust hordes.

But their dream job came to an abrupt end when they both

came down with amoebic intestinal infections that would see them

hospitalized for three months. By the time they recovered and

returned to the U.S., they found that no one could work for any

government program without a security clearance. The patriotic

Chapelles didn't get it. The reason was never known but was

perhaps due to their bigamous state or one of Tony's shady deals.

Dickey enlisted the help of her father, a lifelong Republican but

it was to no avail. A letter from Harold Stassen said that the

services of Mr. and Mrs. Chapelle would no longer be needed by

the Point Four Program. The couple couldn't get work any where,

thereby producing added strain on their steadily deteriorating

relationship. In a letter to her mother, Dickey said, "We weren't

lovers or husband and wife anymore". And despite the difference

in their ages, role reversal took place. Dickey became the mother

and Tony the child. In 1955, the marriage ended though the

relationship never really did.

With her new found independence came fear. Dickey knew it

was up to her now – she had to be self supporting. She

needed a story, so why not approach the guys she loved –

the U.S. Marine Corps.

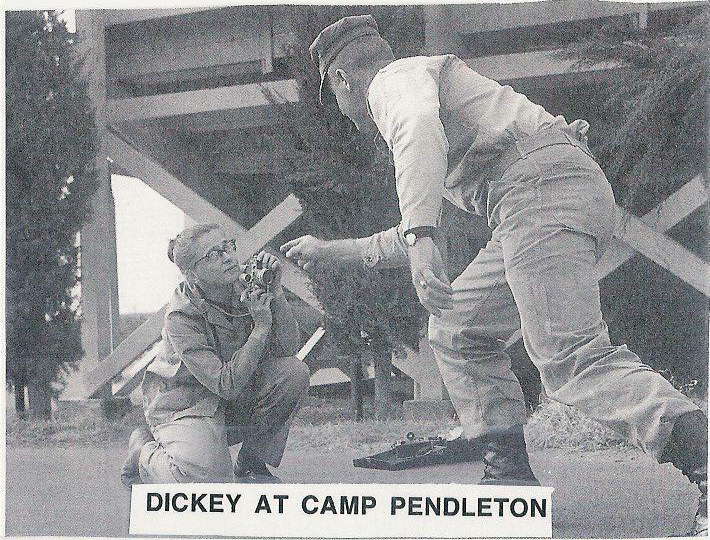

The two Marine generals were less than enthused. Dickey's

proposal to do a story explaining the why and how of Marine

esprit de corps didn't raise any passions because

civilians had never been able to get a feel for just what the

Marine Corps was. But Dickey was undeterred. In her view,

believing a story couldn't be told was just the reason for

telling it. The generals gave her the go-ahead and she

immediately contacted her agent, instructing her to approach any

magazine and tell them she was willing to do a story on

spec (meaning the magazine gives no guarantee of

acceptance) about Marine recruit training at Camp Pendleton,

California. Several months later she got a letter from

a Marine Corps Colonel, giving her permission to do the Pendleton

story. So, she had her story. She didn't have a publisher yet

– but so what. Her real problem was having no money to get

to California. She promised her mother she'd never crawl to Tony

– but she did just that. He loaned her one thousand dollars

and was delighted to do so. She wasn't free of him yet.

It was the resumption of an old love affair – Dickey

Chapelle and the U.S. Marines. "The Marines are one moving

inexorable forward motion. There is a richness and warmth in this

position, that I as a person find in no other." The story didn't

sell.

In July of '56, Dickie received the news that she had been

granted an annulment of her marriage to Tony. In her

autobiography she barely mentions the ending of her non-marriage

as if it was the absolute end of the relationship. But marriage

didn't mean anything to Tony – so why should an annulment?

Just why Dickie went to work for the International Rescue

Committee (IRC) may never be known. But in October of '56 when

the Hungarian revolution was in high gear, Dickie no doubt saw an

opportunity for a story and a way to get back to center stage.

The Committee was originally formed by Albert Einstein, John

Dewey, and Reinhold Niebuhr to help Jews escape from Hitler's

Germany. The rumors of its connection to the CIA probably began

when Wild Bill Donovan, joined the group in the 1950's. Whether

Dickey became a willing spy for the group in Hungary has never

been proven. But considering Dickey's non objective approach to

issues before and after, it's certainly possible. At any rate,

going to Hungary would prove to be an experience that scared her

badly, and some said she was never the same afterwards; though

the record doesn't bear this out.

Dickey's boss at the IRC was Leo Cherne. He and Dickey

travelled to Hungary while the freedom fighters had the

upper hand; ostensibly to deliver antibiotics urgently needed to

combat infection from wounds and illness. Dickey's job was to

record the work of the IRC in Hungary, including Cherne's meeting

with Cardinal Mindszenty, the anti-communist priest who was

residing in the American Legation.

The euphoria didn't last long. Come November, Russian troops

and tanks rolled into Budapest. A cry for American troops went

unheeded and the Communists quickly regained control.

Perhaps Dickey didn't understand the danger she was in, or

perhaps she thought her status as an American would protect her.

At any rate she saw the Hungarian situation as a golden

opportunity. Her adrenaline was pumping, this is what she was

meant to do – come to the aid of oppressed people. In her

usual hyperbolic style, she wrote of "the ache of an uncrossed

bridge, I know the Mongol's ride, Joan burns at every stake". No

doubt it was this attitude that found her on the

Austrian/Hungarian border on a cold winter night with a load of

penicillin meant for the freedom fighters. Had she

stayed on the Austrian side of the border, she might have been

okay, but Dickey was too adventurous for that. Soon she was

trekking deep into Hungary and assisting those Hungarians who

wanted to escape to the west. She would later say she knew it was

a suicide mission, but in reality she thought her papers

identifying her as a relief worker would protect her. The

presentation of the papers had no impact on the army patrol that

took her prisoner.

As Dickey sat in the back seat of the car taking her to a

Hungarian jail, she managed to dispose of the tiny camera that

would mark her as a spy. It was the possession of this camera

that convinced some that she was a CIA spy.

Dickey spent the next seven weeks in a cold dank cell with

one small window through which she was constantly observed.

There were daily grillings but she would not give in to the

accusations of spying; insisting she was merely a relief worker

for the IRC, who'd been arrested while bringing much needed

antibiotics to the Hungarian people. Anytime she felt fear or

cold, she would do a series of rolls she learned from the

Marines. She'd show these commies that she was a tough nut to

crack.

Unbeknown to her, Tony had injected himself into the

picture. 'Here she goes again, getting herself into trouble', he

no doubt thought. I knew she couldn't make it without me. After

her release he told her he'd considered hiring some commandos and

"coming to break you out." Dickey found it amusing that Tony,

with his myriad of health problems and who was now wearing a

pacemaker, thought he was capable of such a venture.

But through the work of the American legation, Dickey was

released. A New York Tribune article reported on

her release with a 31 January 1957 article. "American woman

photographer, Mrs. Georgette (Dickey) Meyer-Chapelle reached the

free world Sunday after fifty days in Hungarian Communist

prisons. She appeared slightly hysterical with 'relief'. Tears

flowed down her cheeks as she said, 'thank God I'm an American.'"

Leo Cherne said, "it was something of a miracle that we got

her out because she didn't have a legal leg to stand on." But

when did Dickey ever worry about legalities. Besides, she was a

celebrity again. The flashbulbs were popping and she loved it.

She was billed as "America's first Cold War hero".

Dickey's star was never brighter as she continually placed

herself in harms way to get the story. Come July '57 and

she was in Algeria where their brand of freedom fighter

was battling the French. And in 1958, she was in Cuba doing a

story for Reader's Digest on a supposed

freedom fighter named Fidel Castro. Like many others,

Dickey was taken in by Castro – for awhile. But by the time

she left the bearded one and returned to the States, she

was quoted as saying, "I hope this revolution doesn't eat its

children".

Of course the revolution did just that, and soon Dickey was

in Florida with anti- Castro Cubans who were plotting the

overthrow of Fidel. She was there as a reporter but that didn't

stop her from helping make bombs and storing nitro glycerine in

her refrigerator. With Dickey the line was forever blurred

between reporting news and making news. Her brother, something of

a demolitions expert, sent her instructions on handling

explosives, because "I knew she was going to do it whether I

approved or not, and I didn't want her blowing herself up".

Of all the criticisms of Dickey, and most are justified, it

could never be said that she wasn't a Patriot. This made her

relationship with Reader's Digest a match made

in heaven. The magazine was much more conservative than it is now

and Dickey's bias in favor of the USA didn't bother them one bit.

As far as they and Dickey were concerned, there was a slave world

and a free world and they knew which side they came down

on.

Not that Dickey was above criticism of her own country. For

one thing, she didn't think military training in our country was

as tough as it should be – and as someone who served in the

fifties, this writer concurs. She blamed it on "The Moms of

America" who didn't want their sons mistreated. Dickey had seen

the enemy and knew what we were up against. "I can't hope to

change what our enemies do. But if I fail to point out where I

believe we are contributing to their victories, I can't live with

me. I'd call this the only patriotic point of view and any

aberrance from it disloyal. I hope I can live up to it."

Around Christmas of 1957, while Dickey was in the

Mediterranean doing a story for the Digest on

the Sixth Fleet, her brother turned on the radio to hear

Evangelist Billy Graham quoting from one of Dickey's stories.

Surely, his sister was now in the big time.

Being in the big time for Dickey meant anytime she was

stateside was in demand on the lecture circuit. She wowed her

audiences in schools, universities, and VFW and American Legion

halls across the country. At each stop she would reiterate her

stand that American youth were too soft. After one lecture she

was approached by two young men who told her they weren't soft

and challenged Dickey to a twenty mile hike. Thirty eight year

old Dickey made the hike with them.

Dickey toured the lecture circuit in a puke pink 1957

Chevrolet. She didn't have a drivers license but Dickey wasn't

going to let a little thing like that get in her way.

The highlight of one lecture tour occurred when she was

taken to lunch by two handsome Marines. She wrote a friend

– "I can't imagine a nicer thing happening to an American

career girl". Marine green was a sure turn on for Dickey.

In June of '58, Dickey was assigned to Beirut, Lebanon and

the camp of Lebanese rebels who were trying to overthrow the

pro-Western government. The rebel leader asked Dickey to relay a

message to the U.S. Marines. "Tell them if they attack, my entire

force will be unleashed against them." Dickey looked around at

his force of maybe three thousand, which included women and

children, and decided her Marines had little to worry about.

Actually the situation in Lebanon was resolved without the

Marines firing a shot.

Dickey first met William Westmoreland at Fort Campbell in

Kentucky on a May morning in 1959. She'd come to do a story on

the 101st Airborne. She was enraptured of the General.

"He looked just like Hollywood would think a general would look."

She took several flights with the paratroopers, each time wearing

a chute and jump boots – it was regulation. But before she

went up, Westmoreland looked her in the eye and said, "You

understand you will not jump." Dickey didn't jump.

But she did jump later, at a parachute school run by an

ex-Army paratrooper. She was petrified but she always employed

her axiom – courage is not the absence of fear but the

control of fear.

In July of 1959, Dickey returned to Fort Campbell, diploma

in hand. She'd been approved by the Pentagon to be the first

woman to jump with the 101st.

By 1961, Dickey was itching to do a parachute jump while

covering a story. John F. Kennedy was now President and a man

after Dickey's own heart. His view of the world was like hers

– black and white – good and evil. Surely he would

see what was wrong and fix it. Camelot was in full bloom

but the bloom soon faded with the disastrous Bay of Pigs, as

Kennedy's indecisiveness assured failure. Dickey couldn't report

on the Bay of Pigs – nobody could – the press was

asked to sit on the story and they obeyed.

Dickey's next and last stop would also turn into a disaster

– Southeast Asia.

Her first assignment from the Digest was the war

in Laos where American Green Berets were assisting the

Royal Lao Army in their battle with the Russian backed Pathet

Lao. It was in Laos that Dickey met Photo Journalist Clancy Stone

(fictitious name) who took it upon himself to show Dickey the

ropes as to how one gets to the front in Laos. "She was anxious

to go," he said. "I really admired her courage. I was with Maggie

Higgins (Marguerite Higgins, who was a photojournalist that most

considered to be better than Dickey) in Korea and she didn't have

a taste for the front the way Dickey did." Dickey was now past

forty but as Clancy said, "I never saw anybody get off on gunfire

the way she did."

One of the first things Clancy did was change her ideas

about good photography that had been implanted by Tony. The

results would show in a story she did for National

Geographic, "Water War In Vietnam". Basically Clancy

taught her that if she thought it was a good shot it probably

was.

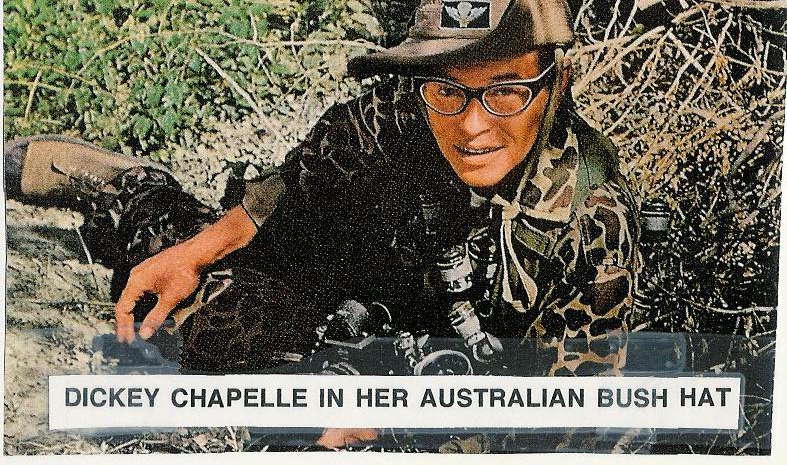

It was Clancy who made Dickey a gift of an Australian bush

hat to protect her from the sun. Thereafter she always wore it on

combat missions.

Dickey's greatest frustration in Laos and Viet Nam was

censorship. Some of her best writing and photos would never see

the light of day. She could see early on that the war in both

countries was being lost but she wasn't allowed to tell the

American people. She believed it was a symptom of her country

losing its greatness. She knew that Americans were not just

advising but actually fighting and dying alongside Laotians and

Vietnamese – and were doing both anonymously.

She wrote the editor of Reader's Digest: "The

little handful of flesh and blood Americans – a few hundred

alive and nineteen dead, wounded, missing, captured – who

I've seen daily risk their lives to carry out policy in Laos.

They're the tough inexorable answer to those who think Americans

today seek adventure by only flipping TV channels. There are

three groups, all volunteer: the veteran transport pilots, the

young helicopter pilots, the U.S. paratroopers of Special Forces,

who lead and teach and die beside Lao soldiers." She was

heartbroken and a little of her died when the

Digest refused to print her words. Her

relationship with the Reader's Digest would

never be the same again. They cared more about not offending the

government than the young men in harms way.

Dickey arrived in Viet Nam in June of 1961. Things weren't

going well. She couldn't even get the title she'd wanted for her

autobiography. She'd asked for With My Eyes Wide Open,

but they wanted What's a Woman Doing Here? It was a title

that set her teeth on edge. Why couldn't it be a book about a

reporter, instead of a woman reporter?

Another of her greatest frustrations was with the Vietnamese

Army. The young men who were dying were good soldiers, dedicated

to their cause, but their officers were incompetent and corrupt.

She couldn't get this printed either.

Dickey was also frustrated with her male peers. Most

resented her even though she took more risk than them on a

regular basis. She filed her stories based on what she'd seen.

They filed theirs from the bars based on what they'd been told by

the Diem government. Indeed, they feared the government that

could pull their credentials for the smallest infraction.

One of Dickey's Vietnamese heroes was not Vietnamese at all,

but a Catholic Priest and former officer in the Chinese

Nationalist Army, named Father Hoa. He commanded a Vietnamese

unit known as the Sea Swallows, which was featured

prominently in Dickey's story, "Water War In Viet Nam". The

Sea Swallows proved they were a match for the Viet Cong

on a daily basis. Dickey loved the Sea Swallows because,

"this is one of the few places in the world where there is only

good and bad, only right and wrong".

Dickey also trusted the Sea Swallows. When they made

combat jumps, she jumped with them, she was now a veteran

paratrooper. She also went on patrol with the Sea

Swallows, through waist deep mud, while looking out for

booby traps and punji sticks. She dreaded patrols more than jumps

because so many things could go wrong.

Communications from the States concerning her autobiography

left her increasingly frustrated. "They've feminized the hell out

of it. What's a person's gender got to do with the way they do

their job!" The book had been sanitized and disinfected. It would

appear Dickey was right. Her autobiography topped out with sales

at seven thousand copies.

When Dickey got back to New York in late 1961, she typed up

a report for Marine Commandant General Wallace M. Greene Jr.,

entitled, "Course of Action, Laos and Viet Nam". He thanked her

for her report and called her a good Marine.

Dickey's seven months in Laos and Viet Nam, where she saw

more of the war than most reporters, certainly entitled her to

voice her opinions, and she did, long and hard. On the lecture

circuit she would tell audiences that South Viet Nam "is as much

my real estate as my home in Minnesota". She was a true Cold

Warrior who believed the line in the sand was South East Asia.

She of course ran into a lot of doubters, such as Mike Wallace

and Jack Parr. When she repeated her opinion that "South Viet Nam

was as much her real estate as her home in Minnesota", Parr

responded, "But isn't the problem the fact that it isn't our real

estate – aren't these sovereign people?"

Another frustration was the fact that many of the photos

she'd taken were still with the censors. She felt like so much of

her hard work done under trying and deadly circumstances had come

to nothing.

Another problem was editors who failed to share her view of

Southeast Asia. Bill Garrett Of National

Geographic viewed Dickey's opinion as too simplistic.

"She was sort of a commie hater and I'd say that's not why we're

there at all." There was a general chorus of disagreement with

Dickey's opinions. But in her defense, she had been on the ground

and they hadn't. Also, if Dickey was wrong, why was so much of

her work censored?

In April of 1962, The Overseas Press Club presented Dickey

with The George Polk Award, the organizations highest. She was

only the second woman to ever win it. She accepted the award

dressed to the nines. One of her friends remarked, "I wish Tony

could see you now."

It was about this time that Dickey decided to deal with some

of the physical problems that had begun to plague her forty-three

year old body. Shortly after, she went against her Physicians

advice and returned to Viet Nam.

By now, there were thousands more American advisors in

South Viet Nam. Father Hoa and the Sea Swallows had been

having a hard time, mainly because of the jealousy of some South

Vietnamese officers. One of Dickey's first duties upon her return

was to attend the funerals of thirty Sea Swallows. To

add insult to injury, they had been killed by U.S. captured

weapons. The funeral marked the beginning of the end of the

Sea Swallows as a military unit.

That afternoon, she was approached by several young Marines

who excitedly told her that they knew of her from their fathers

on Iwo Jima. She was shocked. Had she really been covering

battles that long?

When she returned to the States from her second trip to Viet

Nam she was informed that National Geographic

was going to run her story, "Helicopter War In South Vietnam". It

would be the cover story and would mark the first time a combat

ready Marine was shown in South Viet Nam.

With the Gulf Of Tonkin resolution in 1964, American

involvement in Viet Nam increased dramatically. Dickey was busy

on the lecture circuit telling America that "this was the right

war at the right time" – a rebuttal to the argument against

U.S. involvement in the Korean War. She made her pitch for thirty

thousand more Green Berets to act as advisors to

Vietnamese units. "They're good soldiers but they need

leadership." It seemed she was ready to do battle with everyone.

She lambasted the American government for censorship of reporting

from Viet Nam and was still criticizing America's mothers for

raising sons that were too soft. It was almost as if she had a

premonition that her time was short and she needed to get her

opinions aired.

By August '64, Dickey had another National

Geographic assignment. Fly over the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

At the time Dickey was recovering from surgery on both kneecaps.

She wanted it kept secret lest her jumping privileges be

canceled. Wallace Greene told National

Geographic that Dickey's injuries happened because she

injured her knees jumping with the Army Airborne. Had she

jumped with the Marines, her injuries would never have happened.

In preparation for her next Southeast Asia visit, Dickey

would begin an exercise regimen that would leave much younger

people gasping. She worked out with weights and ran two miles a

day. When she landed in Laos in October of '64, ready for her

visit to the Ho Chi Minh Trail, she felt ready for anything.

It was the time of suicidal monks burning themselves to

death, and her family at home began to worry. Viet Nam seemed so

unstable. Dickey reassured them by downplaying the danger.

It was during this trip to Viet Nam that she met Naval

Lieutenant, Harold Dale Meyerkord, who had become a legend

training the Vietnamese. She spent a lot of time with Meyerkord

in the Mekong Delta province of Vinh Long. They soon became

kindred spirits. Meyerkord gave credit to Dickey for saving his

life when she warned him of a Viet Cong Ambush by firing her

carbine. Of Meyerkord, she would simply say, "He is a man." She

became angry when another reporter was seemingly competing for

the Meyerkord story. The reporter apologized, explaining to

Dickey that he admired her work. "I think she was in love with

the guy (Meyerkord), not in a sexual way but more like hero

worship." Later the young reporter gave Dickey credit for helping

him in his work. "Photographers just didn't help each other

– it was very competitive." He remembered telling Dickey

how he hated traveling in choppers and boats because of the

danger. Dickey reminded him that foot patrols were the most

dangerous.

Lieutenant Meyerkord had forecast his own death. He said it

would be on patrol in the Mekong. Three months later his forecast

came true. Dickey would write, "The audacious, ebullient

Lieutenant Meyerkord – husband, father, leader and teacher

of men – dead of a bullet in the brain on the bank of a

muddy canal." She wrote a letter of condolence to Meyerkord's

widow, the fourteenth such letter she'd written. Meyerkord was

awarded a posthumous Navy Cross.

Dickey came home to Milwaukee in January of 1965 and

immediately took to the lecture circuit, trying to explain Viet

Nam and why we should be there. She further cautioned that the

war was being lost. She ran into her first protesters at the

University of Wisconsin. She was stunned, and in her now raspy

voice, due to too many years of heavy smoking, told them that

Hanoi loved what they were doing. As she was leaving, she said,

"I could turn those kids around, just give me a couple of weeks."

A couple of days later in a Television studio, she was asked what

the country should do about Viet Nam. She yelled out, "Win the

war!"

National Geographic turned down her request to

do another story on the Ho Chi Minh Trail. In a seeming backhand

the editor said that "She was never really that good and she

really had to hustle to keep the work coming." But then he

admitted, "She would stick with a story for two or three months

where another reporter wouldn't stick two days, and she would

bring back the facts, no matter what." One wonders how that

editor could say that Dickey Chapelle "wasn't very good".

In September of 1965, Dickey was given an assignment by the

National Observer to follow a group of Marine

recruits from basic training to Viet Nam. All of her problems

suddenly vanished. She was back with her beloved Marines.

No doubt because of her outspokenness about censorship, Dickey

had a problem getting a visa for Viet Nam. So she called on her

friend, General Wallace Greene. She was ushered into his office

neatly dressed and carrying her Australian bush hat. Greene

looked at the hat and shook his head. Dickey was puzzled and

asked, "What is it sir?" "I don't see any Marine insignia there,

aren't we tough enough for you?" "Oh, no sir, it's not that."

Greene removed his Marine insignia from his collar and gave it to

Dickey. She was speechless with a look of wonderment. "You're

giving this to me sir?" Greene smiled, "I don't think anybody

will mind." As Dickey attached the insignia to her hat Greene

asked, "Why are you going back to Viet Nam?" "Well sir, the

Marines are there and I'm looking forward to covering them."

Dickey left Greene's office in the company of a Sergeant

she'd known for years, who said, "I didn't have a good feeling

about this trip and I could tell she didn't either."

Maybe for that reason, Dickey made one last trip home to

Milwaukee, something she didn't always do.

Dickey landed in Saigon in October, 1965, soon to join the

Marines she'd just seen through boot camp. The American presence

was everywhere, things looked so different.

Those who knew Dickey thought she looked different too. She

was more haggard, always had a Pall Mall between her

fingers and had a bad smokers cough. More than one thought "isn't

she getting too old for this?"

On 23 October 1965, Dickey set off with a combined

ARVN/Marine force on Operation Red Snapper, a search and destroy

mission. As she marched, she talked into her tape recorder. "If

there are bogeymen here, I have no fear as long as I'm in this

company."

On 4 November 1965, Dickey was walking behind a Lieutenant

when he hit the trip wire of a booby trap. The blast hit several

people but the only one mortally wounded was Correspondent Dickey

Chapelle, the only woman correspondent ever killed in combat. As

they knelt over her shrapnel riddled body, someone heard her say,

"I guess it was bound to happen".

Dickey Chapelle was cremated and brought home to Milwaukee.

A Marine honor guard performed at her funeral, an unusual tribute

for a civilian and especially for a woman. One of the honor guard

had been on the same patrol as Dickey and would be immediately

returning to Viet Nam.

The Marine Sergeant who had walked out of General Greene's

office with her attended the funeral along with an Editor from

National Geographic. On the grave site was a

bunch of roses in the name of the Hungarian freedom

fighters. One red rose wrapped in a white ribbon said simply

– "Tony". Taps were sounded.

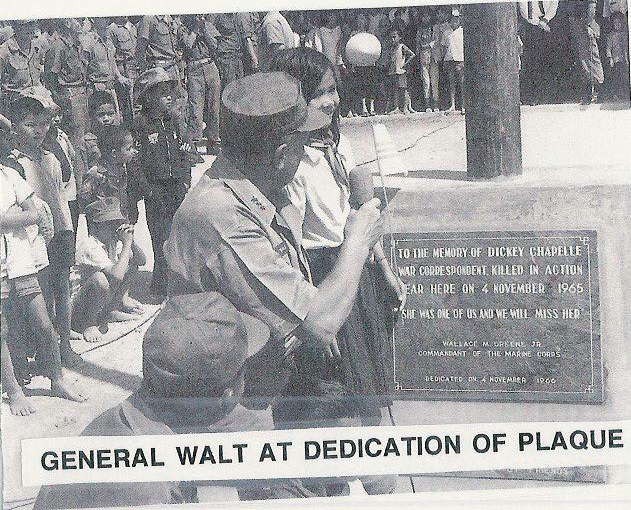

On 4 November 1966, General Lewis Walt came to the village

of Chu Lai, South Viet Nam to dedicate the Dickey Chapelle

Memorial Dispensary. On a marble plaque was this inscription:

To the memory of Dickey Chapelle, War Correspondent, killed in

action near here on 4 November 1965. She was one of us and we

will miss her.

As General Walt stood there, he remembered Dickey's words:

"When I die, I want it to be on patrol with the

United States Marines."

She'd gotten her wish.

Bibliography:

What's A Woman Doing Here by Dickey Chapelle (1961)

Fire In The Wind by Roberta Ostroff (1992)

by Don Haines

... who is a U.S. Army Cold War veteran, American Legion Post 191

chaplain, a retired Registered Nurse, and freelance writer; whose

work has previously appeared in this magazine as well as in

World War Two History, and many other

publications.

|