Fort Blakeley

the Last Major Battle of the Civil War

History generally records the end of the Civil War as occurring

at Appomattox on 9 April 1865, when Robert E. Lee offered his

sword to Ulysses Grant. This probably happened for various

reasons. Most Civil War battles were fought in Virginia, and

surely, the Grant versus Lee was the most famous rivalry of the

conflict. Also, many assumed that if the unconquerable

Lee could be conquered, this would be the signal for all

combatants to lay down their arms. But news traveled slowly

during the Civil War, and while Confederate soldiers in the east

were stacking their arms, four thousand of their comrades in what

was called the war in the west, were preparing for

battle in a place called Fort Blakeley, Alabama.

The Battle of Fort Blakeley was actually the final chapter in the

battle for Mobile, considered by the Union to be the best

fortified city in the Confederacy; protected by a series of

redoubts and forts. But in the Battle of Mobile Bay in August of

1864, three of the major forts, Morgan, Gaines and Powell had

been captured by Union forces, effectively blockading Mobile Bay

and making it impossible for the South to get anything into

Mobile by sea.

It was theorized that with eight thousand men , the city of

Mobile could now be taken. But because of fierce combat in other

areas these troops were not available. The capture of Mobile

would have to wait.

By March of 1865, forty-five thousand Union soldiers were

poised to take the two remaining forts, Spanish Fort and Fort

Blakeley, protecting Mobile. While both were identified as forts,

suggesting walls to be scaled or destroyed, they were actually a

system of defenses, manned by a total of only nine thousand

Confederates. On 27 March 1865, the Union commander, General

Edward E.R.S. Canby, decided to lay siege to the two forts.

Spanish Fort then fell on 8 April.

The troops on either side of this conflict are a story in

themselves. By the end of the Civil War, ten percent of all Union

troops were African-American or United States Colored Troops

(USCT), and on 9 April 1865, at Fort Blakeley,

somewhere between six and nine thousand of these soldiers

participated.

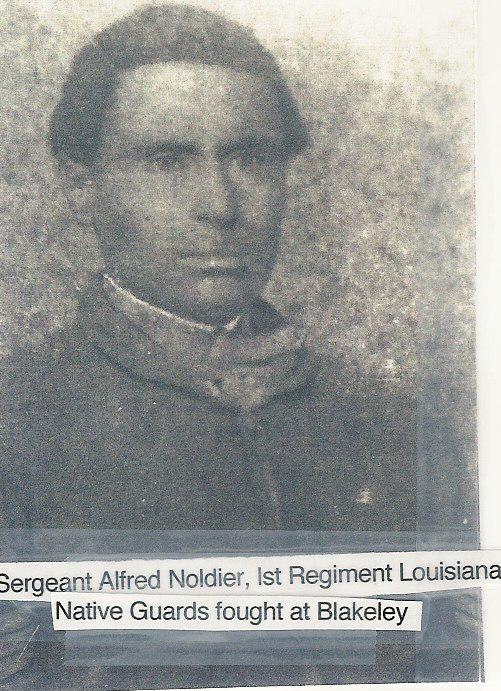

One of the black regiments, the 73rd

USCT was from Louisiana, and originally all of

its members were Freedman from the New Orleans area. They were

land owners, and some were even slave owners, who in the

beginning had decided to fight for the South. But when they

realized the southern hierarchy was using them as a propaganda

tool and had no intention of letting them fight; they offered

their services to Union General Benjamin Butler when the

Yankees took New Orleans after the southern army

evacuated the city.

General Butler welcomed the Native Guard enthusiastically,

now considering them his own propaganda coup. How could the south

complain about arming blacks when the South had shown they didn't

want their black soldiers fighting for them? He further stated

that Officers in the 73rd would keep their commissions

and would now be officers in the Union army. Butler wired

Secretary of War Stanton, and the native Guards were mustered

into the Union army on 27 September 1862, their ranks having been

swelled by escaped slaves from Louisiana.

But black soldiers who joined to fight for their freedom would

soon find that prejudice against them existed in the North as

well. Butler had no intention of using them in combat. The

resistance of white soldiers would be too great, and white

enlisted men would never take orders from a black officer. Butler

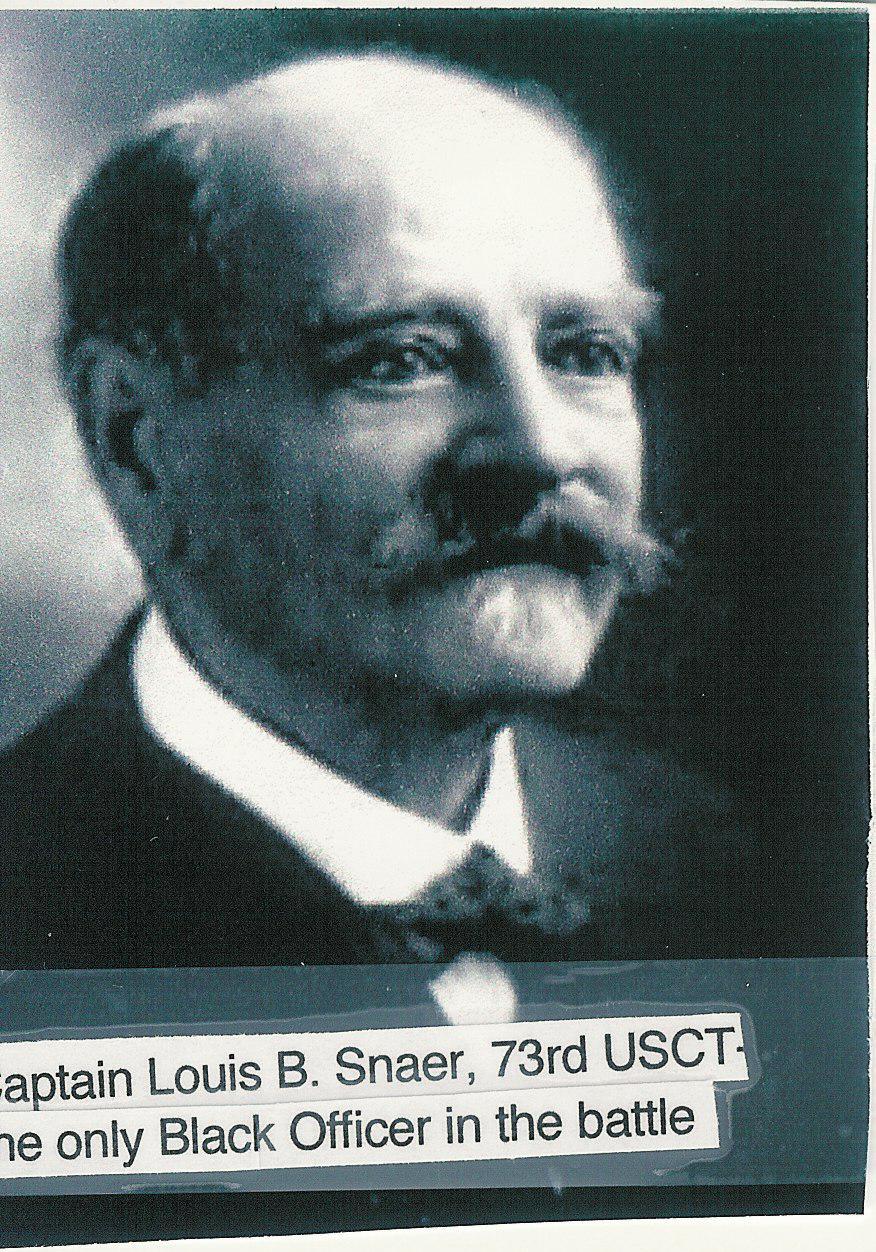

turned out to be right. At the battle of Fort Blakeley, only one

officer in the 73rd, Captain Louis A. Snaer, was

African American. The others had resigned their commissions due

to prejudice. The only black soldiers were enlisted men, and even

for them – as put by one black soldier – it is an

uphill fight.

But by 9 April 1865, as the 73rd got ready to make its

final charge at Fort Blakeley, the black man had proved he could

fight and die just as bravely as his white counterpart. Abraham

Lincoln had put it best when he declared – Why are you

white soldiers so reluctant to shed your blood for the black man

when he so willingly sheds his blood for you.

It was 5:45 p.m. on 9 April when the 73rd

USCT, under the command of rabid abolitionist

Brigadier General William Anderson Pile, charged the Confederate

defenses at Fort Blakeley. A Confederate officer screamed out

– lay low and mow the ground, the damned niggers are

coming. Perhaps the officer who screamed did so because he

knew what to expect. Troops on both sides of the battle had faced

each other before, in the battle for the Tennessee river valley.

It's likely that some of the Confederates had been at Fort Pillow

in Tennessee, where it was said that troops under Nathan Bedford

Forrest had massacred over two hundred black soldiers who were

trying to surrender. Shelby Foote always referred to this story

as – a tissue of lies. But true or not, there can

be little doubt that black soldiers at Blakeley charged with the

battle cry – remember Fort Pillow! What happened

after they carried the day and planted their flag atop the

Confederate works is, like Fort Pillow, still being debated. It's

been said that some Confederates knew what was coming and

scrambled to get away from the black soldiers and surrender to

whites. There was even a report of black soldiers shooting white

officers who were trying to stop the murders.

General Pile, the rabid abolitionist, and one who hated

southerners, said nothing about atrocities in his report. My

men displayed excellent discipline and treated their captives as

prisoners of war. To the Seventy Third Colored Infantry belongs

the honor of planting their colors on the enemy parapet. Some

southerners ran from our troops but they had nothing to

fear. Of course, General Pile was not exactly an unbiased

observer.

The one inescapable truth about Fort Blakeley is that the battle

was over in about thirty minutes. The outmanned and outgunned

Confederates had little chance. But reports of southerners

running from their attackers is also exaggerated. He was still

Johnny Reb, and most Confederates held their ground,

firing and reloading until they fell.

The 73rd suffered three killed and twenty-seven

wounded in the attack, their last casualties of the war. One of

the wounded was the only black officer, Captain Louis B. Snaer,

who received a serious shell wound of the foot during the final

charge. His white commander's report stated &ndashh; Captain

Snaer fell with a serious wound at my feet as I reached the line.

He refused to sheathe his sword or to be carried off the field.

No braver officer has ever honored any flag.

With the fall of Fort Blakeley, the city of Mobile capitulated,

and was occupied by Union troops. The Civil War was finally over.

The 73rd Infantry USCT, which began

as the Louisiana Native Guard, was demobilized on 23 September

1865.

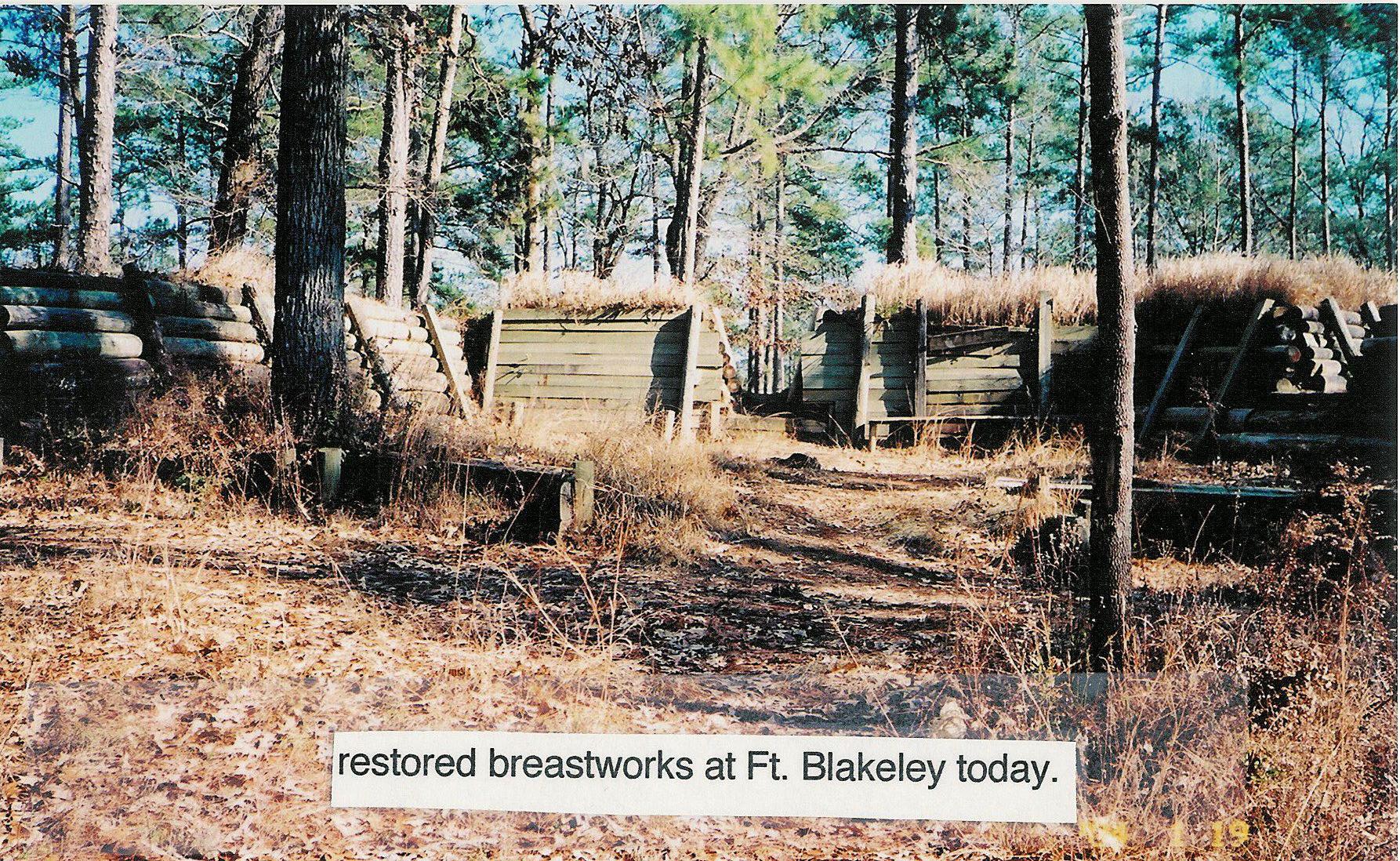

The Civil War that nearly tore us apart one hundred and forty

years ago is still tearing at our national fabric. Fort Blakeley,

in the process of being reconstructed is at the center of a

controversy. There are plans to erect a monument to the

USCT who fought there. There are those who

object because of the supposed atrocities committed by those

troops.

Despite the controversy, the rebuilding of Fort Blakeley goes on

in the Alabama woods because, after all – it was the last

major battle of the Civil War. Or was it? We have another

controversy because there are some who insist that the last

battle was fought in North Carolina. And of course, there is that

skirmish in Texas between Yanks and Rebs in May

of '65 – seems that there were some who hadn't gotten the

message that the war was finally over. The arguments go on.

Perhaps it will help to think of an incident that happened in the

heat of battle at Fort Blakeley. A former slave fighting for the

North found his former master, a Southern soldier. They sat down

and shared a canteen. For them, at least, this was the final

battle.

[editorial note:

Although the Fort Blakeley battle ended on 9 April, that

Confederate department, commanded by LTG Richard Taylor, did not

surrender until 4 May 1865. Likewise, the Sherman-Johnston battle

at Bentonville ended on 21 March, but the surrender was not

accepted until 26 April 1865. The Barrett-Ford battle at Palmito

Ranch, which shared some of the infamy of Pillow and Blakeley,

ended 13 May, but that Confederate department was not

surrendered, by LTG Simon B. Buckner for LTG E. Kirby Smith (who

fled to Mexico), until 26 May 1865. After learning of GEN Lee's

surrender and meeting in tribal council, the last Confederate

command, a cavalry battalion composed of Creek, Seminole,

Cherokee, and Osage Indians, was surrendered by BG Stand Watie on

23 June 1865.]

by Don Haines

... who is a U.S. Army Cold War veteran, American Legion Post 191

chaplain, a retired Registered Nurse, and freelance writer; whose

work has previously appeared in this magazine as well as in

World War Two History, and many other

publications.

|